To Tame Inflation, Talk Isn’t Enough

Central bankers’ proclamations have little effect on consumers—but rate hikes matter more.

To Tame Inflation, Talk Isn’t Enough

Kotryna Zukauskaite

Stanford’s Edward Lazear and Kathryn Shaw demonstrated in 2007 that businesses and other organizations were increasingly relying on group work. Since then, such work has become a mainstay, especially in the technology and engineering industries.

But this brings some challenges when it comes to assigning credit for work well done, the kind of credit that can lead to promotions and raises. Say five people work together on a project. Who did what?

When an employer can’t directly observe each individual’s contribution to a team’s results, demographic characteristics may come into play and affect who gets credit, suggests research by Chicago Booth’s Heather Sarsons, European University Institute’s Klarita Gërxhani, New York University Abu Dhabi's Ernesto Reuben, and University of Amsterdam’s Arthur Schram. Their work finds that employers are more likely to assign credit to men, a pattern that they say contributes to and helps maintain gender segregation in certain occupations.

The researchers turned to an industry they know well: academic economics, which has a large tenure gap between men and women, as well as a growing amount of group work.

To quantitatively assess researchers’ work, Sarsons, Gërxhani, Reuben, and Schram looked at the number of papers produced by academic, research-focused economists who were up for tenure over a 20-year period. They constructed a data set using the curricula vitae of economists who were up for tenure between 1985 and 2014 at 23 of the top PhD-granting universities in the United States, homing in on schools where research was the greatest factor in promotions. They collected historical faculty lists and took other steps to locate anyone who had gone up for tenure.

Sarsons et al., 2020

To assess the quality of work, they looked at the ranking of journals in which those papers were published, as well as the number of times each paper was cited in other research. And to track career trajectory and outcomes, they recorded whether or not the economists in question received tenure.

Then, considering the degree of collaborative work and reward for that work—and after controlling for factors such as coauthor seniority and length of time to tenure—they compared the results for men and women.

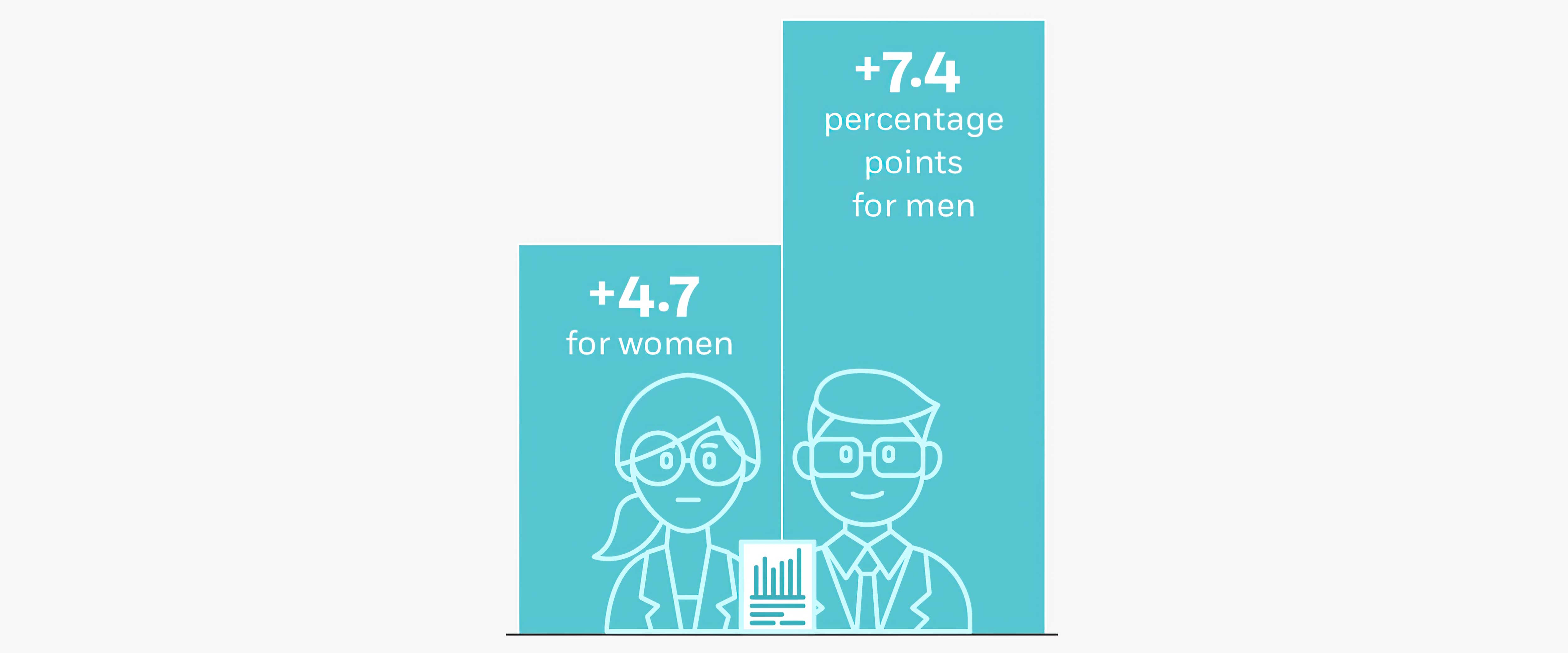

They find that, all else being equal, men and women who solo authored most of their work had similar tenure rates. That changed when the researchers accounted for collaborative papers, however. The tenure gap between men and women became more pronounced the more women coauthored. Each additional piece of coauthored research correlated with a 7.4 percent increase in tenure probability for men but only a 4.7 percent increase for women.

The difference in credit allocation explains 40 percent of the gender gap in tenure rates, the researchers estimate. It also explains 65 percent of the gap that remained after controlling for average paper quality, citations, tenure and PhD institution rankings, and economic subfield.

The gender of a woman’s coauthor may matter, the research suggests. When women coauthored papers with men, they were less likely to receive tenure compared with similarly situated men who also coauthored with men. The gender gap narrowed significantly for women when all the coauthors on their papers were also women.

But that doesn’t necessarily mean that it is better for women economists to write papers alone or only with other women, Sarsons explains. Women are greatly outnumbered in economics, and there are relatively few papers coauthored entirely by women. And besides being impractical, restricting coauthors only to women could potentially have other negative implications.

Rather, workplaces, as opposed to individuals, may draw the most useful lessons from the research. The findings suggest that universities, and indeed all workplaces, need to develop better systems to establish who did what in group work, says Sarsons, who adds that employers need to “slow down and think about whether they’re holding people to different standards.” While it’s difficult to write policies that enforce fair evaluations, doing so could be one step in addressing differences in labor-market outcomes between men and women.

Central bankers’ proclamations have little effect on consumers—but rate hikes matter more.

To Tame Inflation, Talk Isn’t Enough

The podcast explores questions at the heart of recent campus protests—and university governance.

Capitalisn’t: The Economics of Student Protests

A study of two multibillion-dollar retail chains homes in on managers.

A Good Boss Can Boost Team ProductivityYour Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.