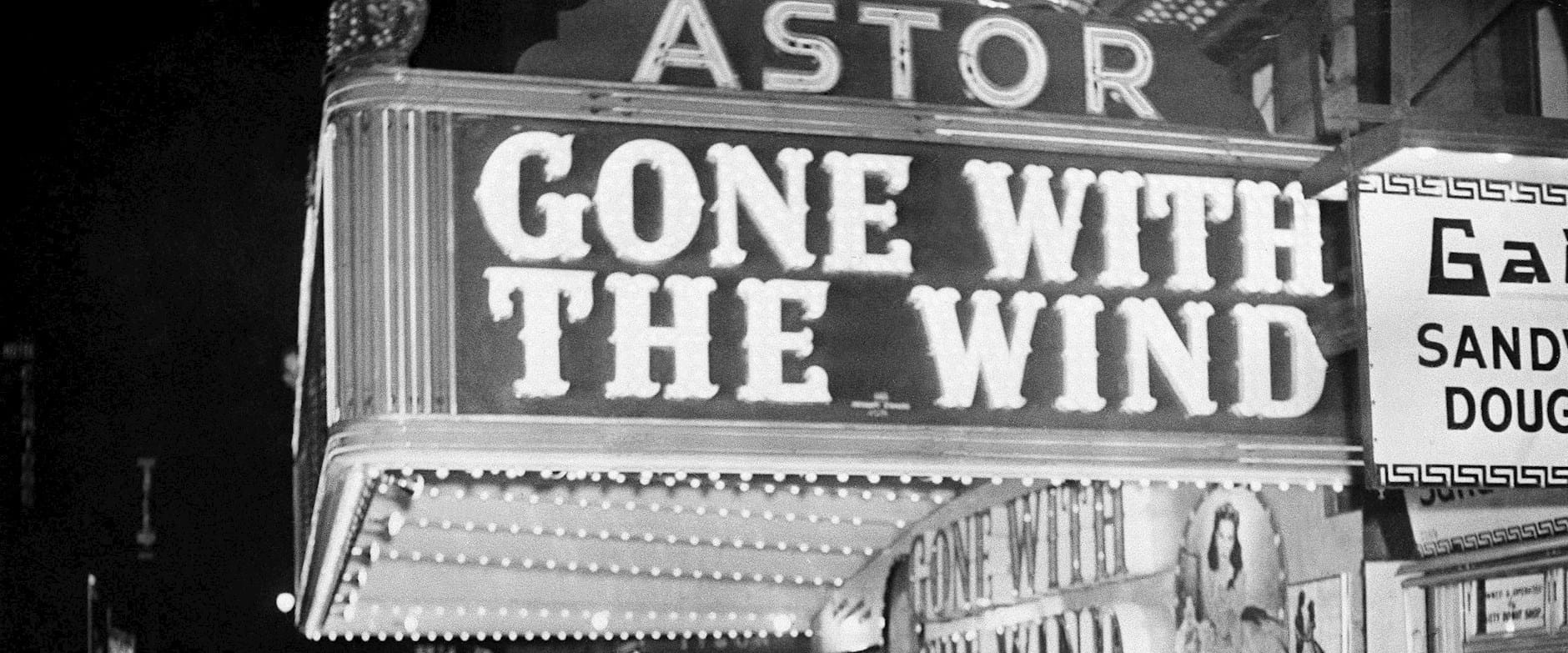

The movie Gone with the Wind depicts a genteel, harmonious world torn apart as the old way of life comes to an end. Behind that gentility was the inhumanity of slavery, whose end transformed the economy of the American South. Morally, that was a good thing, but, contrary to the depiction in the movie, was it also positive for the economy? In this episode, we talk to Chicago Booth’s Richard Hornbeck, whose research with Trevon D. Logan of Ohio State suggests that emancipation created huge economic value, a boost to the US economy that was even bigger than the introduction of the railroad.

Richard Hornbeck: There were a lot of capitalist aspects of slavery in terms of the operation of it as a business, but at its core, it was fundamentally organized around involuntary labor market transactions. And so trying to think about the implications of that and what it would imply for the economic performance of the whole system and in terms of how much was it really delivering aggregate economic gains was something that I felt was important to revisit and just recharacterize.

Hal Weitzman: The movie Gone With The Wind depicts a gentile, harmonious world torn apart as the old way of life comes to an end. Of course, behind that gentility was the inhumanity of slavery. And when slavery came to an end, it transformed the economy of the American South. Morally, that was a good thing. But contrary to the depiction in the movie, was it also positive for the economy? Welcome to the Chicago Booth Review Podcast, where we bring you groundbreaking academic research in a clear and straightforward way. I'm Hal Weitzman.

And in this episode, we're going to take a deep dive into one single research paper with one Chicago Booth researcher. Rick Hornbeck is an economic historian whose new research suggests that emancipation actually created huge economic value, a boost to the US economy that was even bigger than the introduction of the railroad. Hornbeck arrives at that conclusion by analyzing all the costs and all the benefits of slavery and emancipation both to the enslaved and to slaveholders. I sat down with him to learn more.

Richard Hornbeck: My name's Rick Hornbeck, and I'm the V. Duane Rath Professor of Economics at the Chicago Booth School of Business.

Hal Weitzman: Would you consider yourself an economic historian?

Richard Hornbeck: Yeah, I think I've come over time to increasingly recognize myself as an economic historian. I went to graduate school in economics and my background is in economics. My training is in economics. But I think through being in graduate school and just through thinking about different economics questions, I often got drawn more toward a lot of things can be interesting in the immediacy, but what we're often very interested in, how do these things play out over time? So how do people become wealthier over long periods of time?

How do people take advantage of different major opportunities, or how do they mitigate different major challenges? In a sense, just how has the world just become better off, or in what ways has the world become better off over time? And so that increasingly drew me to different historical topics. And I think after I had written or was writing several history papers or several economic history papers, I just realized like, oh, the common theme that connects a lot of the things that I'm interested in is economic history.

Hal Weitzman: You've done some new research on the economics of emancipation. What was your motivation for this project?

Richard Hornbeck: This paper on slavery and emancipation is really a return to a literature that was a very big literature in the past trying to understand what was slavery, how do we characterize slavery, what are its implications. But I think something about that literature always made me somewhat uncomfortable, that that I think it focused very much on the operation of slavery as a business and enslavement as a business enterprise.

And then somewhat inevitably from the perspective of enslavers and not really from a more holistic sense of, well, there's an aggregate economy out there that includes enslavers, but also the enslaved. And they were treated like capital in a sense in slavery, but they were people at the end of the day. And those people's perspectives and the costs they incurred is very much part of the aggregate economy. And so it felt very unsettling, I think, the focus. And so I always felt like there was something that was missing or not emphasized enough.

I think that was one thread. And another thread was just some of my other interests have been drifting toward thinking about misallocation in the economy and different inefficiencies in the economy and the implications of that for aggregate economic growth. And a lot of the work that I've been doing there has looked at ways in which the economy is under providing certain goods or services.

And if something happens like say the rollout of the railroad network that encourages people to produce more, that's going to have extra benefits if the economy is under providing those goods otherwise. So you get this bonus kick for economic growth if you do something that encourages economic activity that was being under provided. And then I was thinking, well, is economic activity always under provided? Will things always have this extra kick? Well, sometimes certain economic activities might be over provided in the market.

There might be too much of certain things. And then if we were to do something that decreases economic activity, that would be particularly beneficial. And I think for me, the obvious example that just jumped out immediately was like, well, what was a thing that was over provided? Well, labor under enslavement was dramatically over provided. That through coercion, enslavers were inducing enslaved people to work far beyond what anybody would voluntarily in a wage system choose or be compensated to work.

And so that was a system where the inefficiency was that people were just being coerced and forced to work and work under conditions that were so intense, much beyond what seemed like it could possibly be efficient. And so then emancipation, in a sense, brought that back. Emancipation brought down labor inputs in the economy. It freed people to work less in a sense, and with that came really phenomenal economic gains that I think have been underappreciated in the literature.

Hal Weitzman: How does your work fit into the broader economic literature on this topic?

Richard Hornbeck: A lot has been written and for a long time. I think back to the Antebellum era, back to the era before the Civil War. Abolitionists and pro-slavery writers were talking about a lot of these issues and trying to characterize how productive is slavery, what would be the implications of emancipation, and so from then to shortly after emancipation all the way up until now.

And I think there was a resurgence of interest amongst economic historians in this probably starting in the... Well, starting somewhat in the '50s and '60s, but particularly through the '60s and '70s with Fogel and Engerman. And the Nobel Prize in part in economic history was given to Fogel along with Doug North, but Fogel for...

Hal Weitzman: That's Robert Fogel, a University of Chicago and Booth economist.

Richard Hornbeck: He wrote a lot on slavery, characterizing the economics of slavery, and I think in a sense the business of slavery, how it operated, how much people ate, how much enslaved people ate, how much they worked, how much they produced, just the data. But reading through these things and thinking about them, there was always something that never seemed to quite hit the mark for me in terms of really getting at the heart of what enslavement was.

Taking seriously this sense in which it was at its heart a coercive institution and was not fundamentally a capitalist economic system in the sense that I think of capitalist economic systems as fundamentally based on voluntary exchange. And there were a lot of capitalist aspects of slavery in terms of the operation of it as a business. But at its core, it was fundamentally organized around involuntary labor market transactions.

And so trying to think about the implications of that and what it would imply for the economic performance of the whole system in terms of how much was it really delivering aggregate economic gains was something that I felt was important to revisit and just recharacterize. I wanted something else that would be like, okay, this is how we really should think about what slavery meant, and then by extension, what emancipation went.

Because I think a lot of people have characterized the South as going into economic decline after emancipation. Output fell in the South. This idea of everything that was gone with the wind after emancipation. It's something about the South had evaporated in a sense. It had left. It's been characterized often as, yes, the moral thing was done in abolishing slavery, but at a cost, the cost of the Civil War, the cost of decreased output afterward.

Output in the South stayed low for a long period of time and eventually started to recover maybe a hundred years... It started to increase substantially maybe a hundred years later. But I think there's a totally different characterization of what's happened in American history, which is that yes, output went down, but it was a phenomenal increase in aggregate economic performance when you think about the enslaved people as people really part of the economy and part of society.

And so this wasn't a decline in a sense. This was actually just a dramatic gain for the aggregate economy that we as a country have been looking to build on it and can continue to build on through racial progress since and hopefully continued racial progress. I think I'm still myself trying to understand all of the different ways that the characterization of slavery is so important to people.

And I think at its core it's because it's just so foundational to what our country was before the Civil War, and what the Civil War and emancipation meant just set the country on just a wholly new better trajectory afterward and just opened up all these potential gains subsequently. And so thinking about all of the gains that came about through emancipation, that's reflected in I think the recent focus on, for example, like Juneteenth as a holiday and what that means.

I think still is thought about as, well, it's a holiday for emancipated people. It's a holiday for formerly enslaved people, descendants of formerly enslaved people. And it's a tremendous celebration of gains to them, but not just to them, to the aggregate country as a whole, because they're very much part of that aggregate country. And so that's why we're thinking about this as really a boost to the aggregate performance of the overall US economy and the country.

Hal Weitzman: And just since you mentioned Robert Fogel, who, of course, I should also mention was a Nobel laureate, right? Am I right in remembering that Fogel's basic insight or basic premise was that while slavery was immoral, it was productive? Because previously, I think, I'm right remembering that people had said slavery was... The whole system was an economic collapse. And he went through careful documentation to show actually it was very profitable for slave holders. Isn't that right?

Richard Hornbeck: Yeah, I think some people had made that argument before him, but there certainly had been a characterization... One characterization of slavery is that it was this stagnant economic system that didn't really exist for economic purposes. It was more of a mechanism of social control. And actually the beginnings of that argument was actually in a lot of abolitionists writings prior to the Civil War where abolitionists were arguing that, look, this system isn't even that great for the South.

That maybe everyone would be better off if slavery were abolished. Adam Smith makes an argument that slavery is really not productive because people that are working for somebody else, people that are coerced to work for somebody else, will never have that same incentive, will never have that same drive to produce that a free worker would. And so that argument has been around for some time.

And Fogel and others, I think, convincingly argue that no, actually coercion can be very effective at inducing people to work much more than they would want to voluntarily, and it can induce a lot of output. One of the particularly controversial quantitative points that they made is they argued that enslaved people received 90% of what they were producing in the form of food and shelter and clothing and different consumption goods.

And so Fogel and Engerman compare that provocatively to tax rates, and they say, "Well, look, a lot of people pay higher than 10% in taxes and they're not considered to be incredibly coerced." They make that comparison. And one thing we argue in the paper is that it's really just the wrong focus. The wrong thing to focus on is how much did enslaved people receive as a share of what they were producing, because what they were producing was in no way connected to the costs that they were incurring.

Really, the much better measure to focus on is, well, what were enslaved people receiving as a share of the costs that they were incurring, and that's much lower. We calculate something more in the order of 7%. They were receiving maybe 7% of the costs that they're incurring. And slavers were receiving about 7% as well in the form of surplus output that they were keeping and stealing in a sense. And then 86% of it was just completely lost, had just evaporated in this extra cost that people were being forced to incur that they weren't actually even producing any output from.

And that's the sense in which we characterize slavery as not just theft, it's not just enslavers taking enslaved people's output from them through coercion, it's inefficient theft. That for every dollar that they're taking, they're losing a tremendous amount of that in the process. And that's the sense in which slavery is inefficient, is that it's not just a transfer of wealth from one person who should rightfully have it to another, it's a transfer that loses a tremendous amount along the way.

Hal Weitzman: Okay, I want to get into the model where you actually calculate. Your economic boost of emancipation that you calculate is somewhere between 4% of GDP and 35%. Is that right?

Richard Hornbeck: Yes.

Hal Weitzman: Why is that such a wide range and how did you arrive at that figure?

Richard Hornbeck: The actual calculations themselves is a very wide range because there's a wide range of costs of enslavement that someone could potentially consider. At what price would somebody voluntarily allow themselves to become enslaved is not a well-defined concept. And so some of the smaller numbers reflect more limited calculations, things like the premium that people might be paid after emancipation to work under that intense gang labor system. They were often offered a salary maybe two and a half times what the base typical salary would be.

And still they were often unwilling to work under that gang labor system. So if you think about, okay, well, if that was the cost of enslavement, the fact that you wouldn't be... If a general agricultural income at the time per capita might be $40, $100 would be the gang labor premium. And so if you think about the cost of enslavement to people was $100 on that annual basis, then you could do that calculation and you would find about... And that $100 exceeds the value that enslavers were actually receiving from enslaved people.

They were receiving more on the order of $60, maybe roughly $30, and this is a bit high perhaps, but let's say $30 went to enslaved people in the form of consumption and clothing and shelter and things like that, and then $30 was captured by the enslavers themselves. And that $30 was reflected in the market value of enslaved people, which was very substantial. If you have an asset that pays you $30 every year, that asset is going to have some substantial value. And so $30 is going to enslavers, $30 is going to be enslaved, that's $60, but $100 of cost is being incurred.

And so $40 is being lost. For every enslaved person, $40 is being lost. And there were four million enslaved people. And so four million times $40 is the boost that the aggregate economy just recovers when it does away with this inefficient institution. That generates an aggregate economic gain that's worth the equivalent of around 4% of GDP. So it generates the same boost that some new technological innovation would that would generate 4% of GDP.

It's an interesting number because it's actually in excess of some of Fogel's other calculations that calculate the aggregate economic gains from the entire railroad network and finds a number that's somewhat less than 4% of GDP. So already with that small number, in a sense, it's one of the more important technological innovations in a sense in US history. But that number, that gang labor premium is really far insufficient to capture all of the costs incurred under enslavement.

There's just the loss of agency over time, over where you're going to live, what you're going to do outside of traditional so-called working hours. People were not free to enjoy their lives as they might see fit.

Hal Weitzman: So how do you account for those bigger costs that slavery imposed?

Richard Hornbeck: It's prohibitively difficult to think about going through all the different atrocities of enslavement and just assigning some costs to them, adding them all up. The frequency of whippings and the fear of whippings was very salient, and it's very salient in narratives of formerly enslaved people as they're describing freedom and they're describing the cost of enslavement. It's very salient to them, but how do you even start to go about adding all of that up? And so a literature that we draw on there is a literature associated with the value of statistical life.

That while it's hard to think about the cost of enslavement, it's also similarly hard to think about the cost of death in a sense. But we often have to think about the cost of death when we evaluate what should speed limits be. We know if people are allowed to drive faster on highways, there will be more highway fatalities, but people get places faster. And so there's some trade-off there.

Or when we evaluate how much pollution is going to be allowed in the atmosphere or what levels of pollutants are going to be allowed, elevated levels of pollution contribute to infant mortality, contribute to various respiratory problems, elderly health issues. So the economy overall accepts some trade-off between economic value and death. And the language that economists sometimes used to think about that is, well, what trade-off is being made?

They associate with this idea of value of a statistical life, that there's some economic value that's lost when people die and guides trade-offs that people themselves make when they think about whether to take on a riskier job versus a less risky job when people decide how fast they're going to drive, when people decide various medical decisions. And so that value of statistical life is hard to quantify, but is often roughly some multiple of people's annual consumption or annual income, maybe 100 to 200 times annual income.

For example, say it's 100 times, somebody with an annual income of say $60,000 a year, it would be looking at say $6 million as a trade-off of, okay, somebody might be willing to accept say a 1% chance of mortality in exchange for $60,000. Everyone will have a different trade-off that they're willing to make, but those things are embedded in that. And so we took that idea of like, okay, that's some economic value that people associate with their lives.

And certainly under enslavement, there was a lot of discussion amongst enslaved people after they were freed of the costs that they were incurring and desire to escape toward freedom, but the various impediments to escaping toward freedom that a lot of people were willing to endure worse than death to try to keep their family safe and their partner, their kids, their extended family.

And so there's been a characterization of slavery as social death. That in a sense it's just the taking of people's agency, the taking of their lives. And here we're drawing on somewhat more of a humanities tradition as well of thinking about these different embedded costs of enslavement.

Hal Weitzman: So how do you use that idea, that idea of social death in your research?

Richard Hornbeck: If we think about, okay, say this value of statistical life is often 100 to 200 times annual consumption, take the $40 of annual consumption that a free person would be earning at that time in the agricultural sector, multiply that by say 150 to get an implied value of statistical life. On an annualized basis, that generates a cost of around $420 at a 7% interest rate. And that $420 you could think about is like, well, that's the annual cost that people were really incurring, not the $100 gang labor premium or something a little bit more when you're adding that value of time.

The $420 reflecting that loss of agency over their lives. And that $420 relative to the $60 that was being produced is now a more substantial $360 per enslaved person. And take that $360 and multiply it by the four million enslaved people, 13% of the US population at that time, you're going to get a very large number relative to GDP, and that's where the 35% comes from.

Hal Weitzman: Just explain to us, what do those numbers really mean? What would it mean to say that emancipation boosted the economy by the equivalent of 35% of GDP?

Richard Hornbeck: These calculations aren't so much that this is an exact number that you would take, but more of a conceptual shift in just the overall economic performance of enslavement and emancipation. And what emancipation really fundamentally did was just launch forward the aggregate US economy and bring about these just tremendous gains that haven't been fully appreciated. And so the end of slavery and emancipation is not this period of economic loss.

It's this tremendous leap forward that then creates opportunities for further advancement with declines in racial discrimination, with declines in racial harassment. There's further gains as well. Because a corollary to a lot of these ideas is just the inefficiency of say, for example, racial or sexual harassment as well. It's true that some people might have a preference for being racially discriminatory, or some people might have a preference for sexual harassment, for inflicting sexual harassment.

But in general, the costs that are incurred by people that are harassed or discriminated against are much larger than the gains to the person doing the harassment. And so it's also similarly just this incredibly inefficient activity that maybe it's generating some gains for somebody, but it's imposing such larger costs on others. And so that's the sense in which it's not just about comparing some people's welfare to other people's welfare, it's also just on this direct trade-off an incredibly inefficient way of taking something from somebody that so much is being lost along the way.

And this notion of efficiency or what's efficient or inefficient, it's not synonymous with what's moral or correct or what should be done. Economists are sometimes odd people. When economists say something's efficient, they don't necessarily mean that things should be done. It's just a way of describing some aspect of its characteristic, but we can think about something as being efficient or inefficient.

Hal Weitzman: Rick Hornbeck, thank you so much for coming in and talking to us about your work. That's it for my interview with Rick Hornbeck. You can find a lot more about the economics of slavery and its legacy on Chicago Booth Review's website at chicagobooth.edu/review. When you're there, sign up for our weekly newsletter so you never miss the latest in business focused academic research. This episode was produced by Josh Stunkel. If you enjoyed it, please subscribe and please do leave us a five star review. Until next time, I'm Hal Weitzman. Thanks for listening to the Chicago Booth Review Podcast.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.