Michael Byers

How to Profit from Magical Thinking

- By

- May 15, 2017

- CBR - Behavioral Science

At NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, in Pasadena, California, where the space agency manages many of its mission launches, the control room features a display case with a container of Planters peanuts, a testament to magical thinking in action. The peanuts first appeared in the lab as a snack in 1964, as the Ranger 7 spacecraft prepared to launch. After six failed launches, “I thought passing out peanuts might take some of the edge off the anxiety in the mission operations room,” says Dick Wallace, a mission trajectory engineer, in NASA’s official account of the “lucky-peanuts” tradition.

That day went well, and the peanuts became a fixture for several decades—until the next generation of engineers forgot the tradition’s significance. In 1997, the Cassini mission to Saturn was slated to launch on October 13, but was rescheduled due to poor wind conditions. Then someone remembered the peanuts and realized there weren’t any in the room. When the countdown eventually started two days later, the engineers in the control room snacked on peanuts once again.

NASA engineers are highly trained scientists, and data would refute any possibility that launch success relates to what snacks engineers eat. But that hasn’t stopped NASA employees from bringing peanuts to countdowns and even enshrining them in a display case. In doing so, the scientists trained in evidence-based analysis bow to tradition that binds them to previous launches—and don’t take chances that could, in any remote way, affect the outcome of a mission.

“We’re not superstitious,” insists a representative for NASA, who says engineers don’t actually believe in any peanut power on mission outcomes and do veer away from the peanut tradition on occasion—on the 2016 Juno mission arrival at Jupiter, for example, “done with no peanuts in mission control.”

Superstition is believing, erroneously, that there is a causal connection between two things, even when it’s obvious that they are not related, says Chicago Booth’s Jane L. Risen, who studies the psychological underpinnings of phenomena such as superstition. “It goes beyond just being wrong to believing something that is scientifically impossible.” Superstition, which tends to be associated with creating good or bad luck, is closely related to magical thinking, which Risen describes as “the belief that certain actions can influence objects or events when there is no empirical causal connection.”

Rather than focusing on people’s cognitive shortcomings, some accounts of superstition focus on people’s motivations.

While many educated people may call such thinking silly and old fashioned, they also consider it unwise to discount. Hence people worry about knocking over a saltshaker but throw salt over their shoulder for good luck. They walk around ladders, avoid black cats, pick up pennies, and handle mirrors with care. And researchers observe people are also thinking magically about real estate, the stock market, and other areas of business.

Their findings could be useful for managers, marketers, and investors. . . . Knock on wood.

Why so superstitious?

Business and government leaders like to act strategically, or presume they do. But in many cases, their decisions—business, and personal—are informed by superstition, research suggests. After Hurricane Katrina, for instance, New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin blamed the storm’s havoc on the wrath of God. He could have, more rationally, blamed it on people “for not maintaining the proper safeguards for a city of that size,” says Boston University’s Carey K. Morewedge.

Consumers, too, can be guided by superstitious beliefs. In Chinese culture, the number four, which sounds like the word for death, is avoided, while eight, nine, and six are considered lucky. Research by a team from Georgetown University, Nankai University, and the National University of Singapore suggests that ethnic Chinese residents of Singapore are less likely to buy a condo ending in the unlucky number four, or one that resides on the fourth floor, while they’re more likely to buy units ending in the lucky number eight. People who lived in both kinds of units had car accidents at about the same rate, one indication that home numbers did not confer luck and were instead simply subject to superstition. These superstitions had real consequences. Prices for units ending in four were discounted by 1.1 percent, while units ending in eight commanded a 0.8 percent premium.

Lucky numbers can affect home prices

Taking advantage of uniformity in address numbers in Singapore’s high-rises, researchers find that home buyers’ consideration of the unlucky four and lucky eight shows up in sale prices.

When Chinese companies select dates for initial public offerings, they pick dates containing lucky numbers more frequently than statistics would expect, according to University of California, Irvine’s David Hirshleifer and Ming Jian and Huai Zhang of Nanyang Technological University in Singapore. Chinese companies also tend to pick telephone numbers with lucky numbers, says Zhang.

Traditional accounts of superstition insultingly blame superstitious beliefs on irrational or “primitive” thinking, but the fact that so many people hold superstitions—including NASA engineers—suggests that there is more to them. Researchers at Chicago Booth’s Psychology of Belief and Judgment Lab, among other places, are looking into a number of psychological phenomena surrounding magical judgments. Some explanations:

It’s a way to gain control over the world.

Rather than focusing on people’s cognitive shortcomings, some accounts of superstition focus on people’s motivations. People believe and do things that go against logic in an attempt to understand and gain some semblance of control over the world, says Boston University’s Morewedge. “People tend to blame others more often for their negative outcomes and take responsibility for their positive outcomes,” he says. Magical thinking might come into play if you don’t get a promotion at work. You might determine that someone, perhaps an angry coworker, is impeding your progress.

This relates to a shared quest to explain our surroundings and regulate the uncertainty of our lives. Why has this stock gone up or down? Why isn’t my computer working? People believe things happen because there’s some design to our lives, design that goes beyond more rational explanations such as technological malfunctions. To some degree, we want to think events or outcomes have deliberate causes. “Attributing intentionality to an outcome allows you to feel you have control over it,” Morewedge says.

This applies to things as well as events. He finds that people are more likely to anthropomorphize a car or a computer if it’s acting unreliably. The owner may think the machine has a mind of its own, or that it’s been hacked. On the flip side, using random games such as Rock, Paper, Scissors, Morewedge finds that people think they can perform at their highest level when in the presence of a lucky object. “When they use these items, they have greater confidence that they can achieve performance-based goals,” he says.

Other research finds that people who don’t necessarily believe in karma nevertheless do good deeds for others in order to spark good outcomes for themselves.

Someone waiting for important news—such as a job offer or the results of medical tests—may think it wise to build up her karma bank so that the universe will reward her with the outcome she wants, according to research by University of Virginia’s Benjamin A. Converse, Risen, and Colby College’s Travis J. Carter. “When wanting and uncertainty are high and personal control is lacking, people may be more likely to help others, as if they can encourage fate’s favor by doing good deeds proactively,” they write.

A series of experiments tested this hypothesis, both in the lab and at a job fair, where the researchers looked to see under what conditions people were more likely to donate to charity. Their findings suggest that people invest in good karma when they want to get something in return that they know they can’t control. “People may proactively invest in [magical] systems in the hopes of improving their outcomes,” the researchers conclude.

There’s nothing to lose.

Research also suggests that people who ostensibly know better succumb to superstition “because they have nothing to lose by doing it,” says University of California, Riverside’s Thomas Kramer. He sees magical thinking as related to the psychological belief of contagion, where objects exchange properties by way of touch or proximity. “[In contagion,] if a smart person touches a pen, some of that smartness transfers to the pen and to me,” he says. Along the same lines, some areas of homeopathic and alternative healing draw their purported impact from the idea that things that are alike share properties, which he says explains why some people in Asian cultures still adhere to the ancient belief that drinking the blood of a snake will increase strength and sexual prowess—with practitioners believing any short-term discomfort will have no lasting negative effects, and be outweighed by lasting positive ones.

Dual systems of cognitive thought

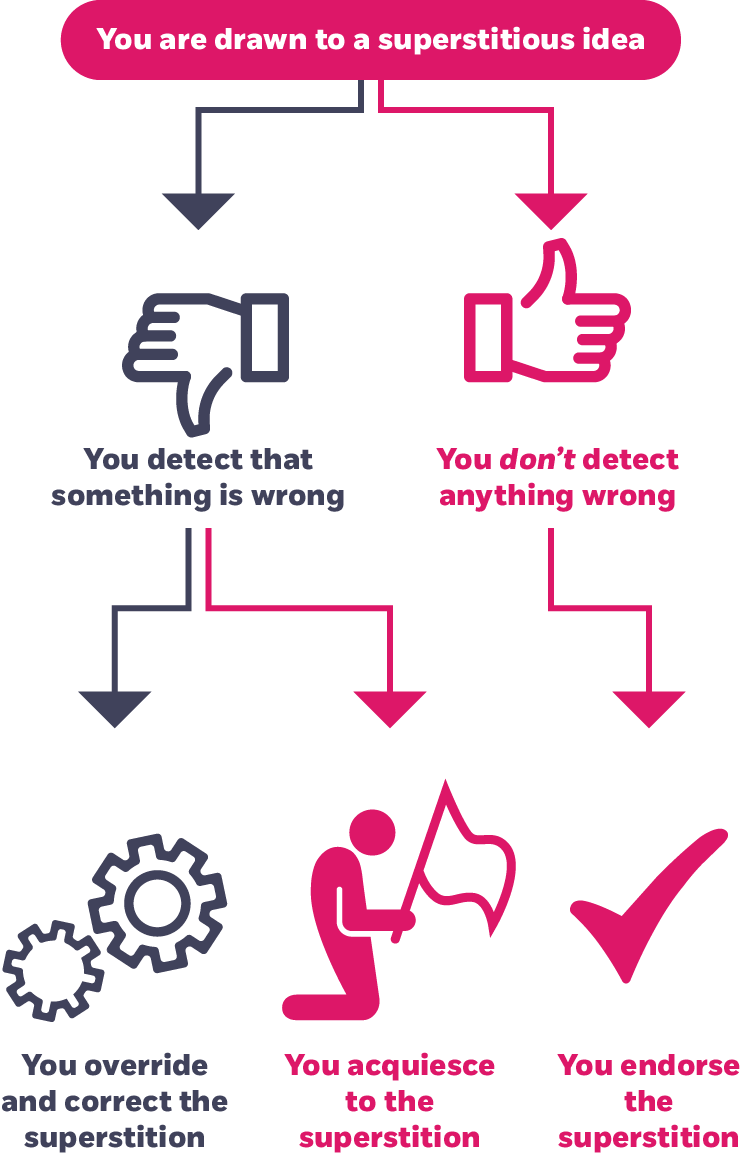

All people are susceptible to superstition, says Chicago Booth’s Jane Risen. Unlike other models, hers suggests that people can maintain superstitious beliefs that they explicitly recognize are illogical.

Risen, 2016

For a more peaceful example, many public and private spaces adhere to the design principles of feng shui, a Chinese belief system that attributes a location’s energy flows to the organization of buildings and design elements. Adherents believe that arranging the office, for instance, according to feng shui rules will help achieve certain goals, including reducing anxiety and uncertainty. If you manage an office, or sell real estate, why not use it, by moving a doorway or locating a desk in a specific orientation? “If you believe in it, there’s much to gain; if it doesn’t work, then you don’t lose much,” says Kramer.

Our minds automatically see connections even when they aren’t there ...

The psychology guiding superstitious behavior is fundamentally the same as the psychology behind any other intuition that’s wrong. “We’re trying to understand the world and figure out what causes what,” Risen says. It’s easy for people to pair two occurrences and assume a correlation. For example, a baseball fan might assume a correlation between the fact that he wore red socks and the fact that his favorite baseball team won a game. Sometimes correlations may be accurate. Some may have a seemingly logical explanation but be wrong. And some may be unquestionably, definitely wrong—which can be described as magical thinking.

Risen suggests that a basic, dual-process model for cognition can help explain why all people are susceptible to superstition, building on the ideas of Princeton’s Daniel Kahneman, who won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 2002. Kahneman describes two ways of making judgments: a “fast” way that builds on patterns you’ve seen before and other mental shortcuts, or heuristics; and a “slow” way that takes a more reasoned approach, correcting the “fast” errors that crop up. Our fast approach to making judgments is especially likely to lead to superstitious intuitions. If slower processes don’t recognize that the intuition is scientifically impossible, then it may guide behavior.

For example, Cornell’s Thomas Gilovich and Risen chronicle “a widespread belief that it is bad luck to tempt fate, even among those who would deny the existence of fate.” This manifests itself in people who carry umbrellas to ward off storms and who shy away from bragging and counting their metaphorical chickens before they’re hatched. The researchers identify basic “fast” cognitive processes responsible for these beliefs—the tendency to allow negative possibilities to capture our attention and to take the ease with which something jumps to mind as a cue for determining its likelihood. But even as people avoid behaviors thought to tempt fate, they may “shake their heads and roll their eyes, knowing that their behavior and worries are unwarranted,” the researchers write.

... and even when we know they aren’t there.

Risen says Kahneman’s basic model works, but it doesn’t explain why subjects can know something is irrational and choose to do it anyway. While the basic model quite reasonably assumes that people will correct their mistakes if they detect them, Risen suggests that magical thinking is one domain where people will sometimes maintain intuitive beliefs that they know are wrong. Thus, Risen’s model separates the detection of a fallacy from whether people correct it. A sports fan may know that his attire can’t affect the outcome of a game, for example, but he’ll still feel compelled to wear his lucky socks—and he’ll feel more optimistic about the game because he’s wearing them. Risen is continuing to test how people can maintain magical (and nonmagical) beliefs that they know are false, and how people can change their beliefs and behaviors when they recognize that those beliefs aren’t sensible.

Benefiting from magical thinking

Understanding how these sorts of cognitive biases work can help people understand when they are perpetuating erroneous beliefs themselves, and how to capitalize on them.

Say you know an executive who always wears his “lucky suit” when making a pitch to investors. He may attribute his skill in raising money to the suit itself, and discount or fail to recognize the other factors, such as preparation, that have more influence on the success of a pitch session. If he understands that he is looking for ways to gain control over the world, he may be willing to wear a different suit to a pitch and see if he is just as convincing. That could ultimately help because he will truly have more control over pitch sessions.

Developers in Chinese markets can cash in on these belief and behavior patterns by adding more units with lucky numbers and renumbering unlucky ones. Product managers can try integrating lucky characteristics, as dictated by superstition, into products—or avoid a bad-luck date for a product launch, Kramer suggests. (On the flip side, his research into lucky colors and numbers finds that “they work because they set up expectations.”) Widely held superstitious beliefs can create an expectation in the market, so that home buyers are comfortable paying more for lucky-number properties and are able to resell them later for more as well.

Seeking luck in the stock market

Studying stocks traded by Chinese investors, the researchers find that companies try to aid their fortunes by securing lucky listing code numbers on the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges.

| At least one unlucky four and no lucky digits | At least one lucky six/eight/nine and no unlucky four |

Hirshleifer et al., 2016

Investors could gain by recognizing how biases can cause market distortions. Hirshleifer, Jian, and Zhang looked at how lucky numbers affected stocks listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges between 1990 and 2013. Analyzing the stock listing numbers of Chinese companies, they find evidence that when a company’s listing code—its numerical ticker symbol on the exchange—contained more lucky numbers, the return to the stock around the IPO date was higher. But when people bought seemingly lucky companies with less regard for fundamentals, stocks went on to underperform. In the first three years after an IPO, investors saw about 11 percent lower returns each year for lucky-number companies than for unlucky-number companies, the researchers find.

In addition, they find that some companies appeared to recognize and benefit from the bias. A higher proportion of companies’ listing codes had lucky digits than could be explained by a normal distribution, and companies with larger IPOs were more likely to have lucky-number codes (the stock exchanges don’t have a formal procedure for assigning these codes). The researchers surmise that larger companies have the political heft to demand better listing codes.

Executives should pay attention to culture, including regional superstitions, when making marketing decisions, Zhang advises. “We believe it’s universal that superstition will have an impact on people’s behavior,” Kramer says. “Superstitions allow you to deal with uncertainty and there is always uncertainty. They will always play a role.”

- Sumit Agarwal, Jia He, Haoming Liu, I. P. L. Png, Tien-Foo Sing, and Wei-Kang Wong, “Superstition, Conspicuous Spending, and Housing Markets: Evidence from Singapore,” Working paper, March 2016.

- Benjamin A. Converse, Jane L. Risen, and Travis J. Carter, “Investing in Karma: When Wanting Promotes Helping,” Psychological Science, October 2012.

- Eric J. Hamerman and Carey K. Morewedge, “Reliance on Luck: Identifying Which Achievement Goals Elicit Superstitious Behavior,” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, November 2014.

- David Hirshleifer, Ming Jian, and Huai Zhang, “Superstition and Financial Decision Making,” Management Science, forthcoming.

- Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow, New York: Farrar, Strauss, Giroux, 2011.

- Thomas Kramer and Lauren G. Block, “Conscious and Nonconscious Components of Superstitious Beliefs in Judgment and Decision Making,” Journal of Consumer Research, April 2008.

- ———, “Like Mike: Ability Contagion through Touched Objects Increases Confidence and Improves Performance,” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, March 2014.

- Jane L. Risen, “Believing What We Don't Believe: Acquiescence to Superstitious Beliefs and Other Powerful Intuitions,” Psychological Review, August 2015.

- Jane L. Risen and Thomas Gilovich, “Why People Are Reluctant to Tempt Fate,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, March 2008.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.