Look Beyond Your Own Experience

Let the events of your life enrich, not bias, your thinking.

Look Beyond Your Own Experience

Bae Crespo

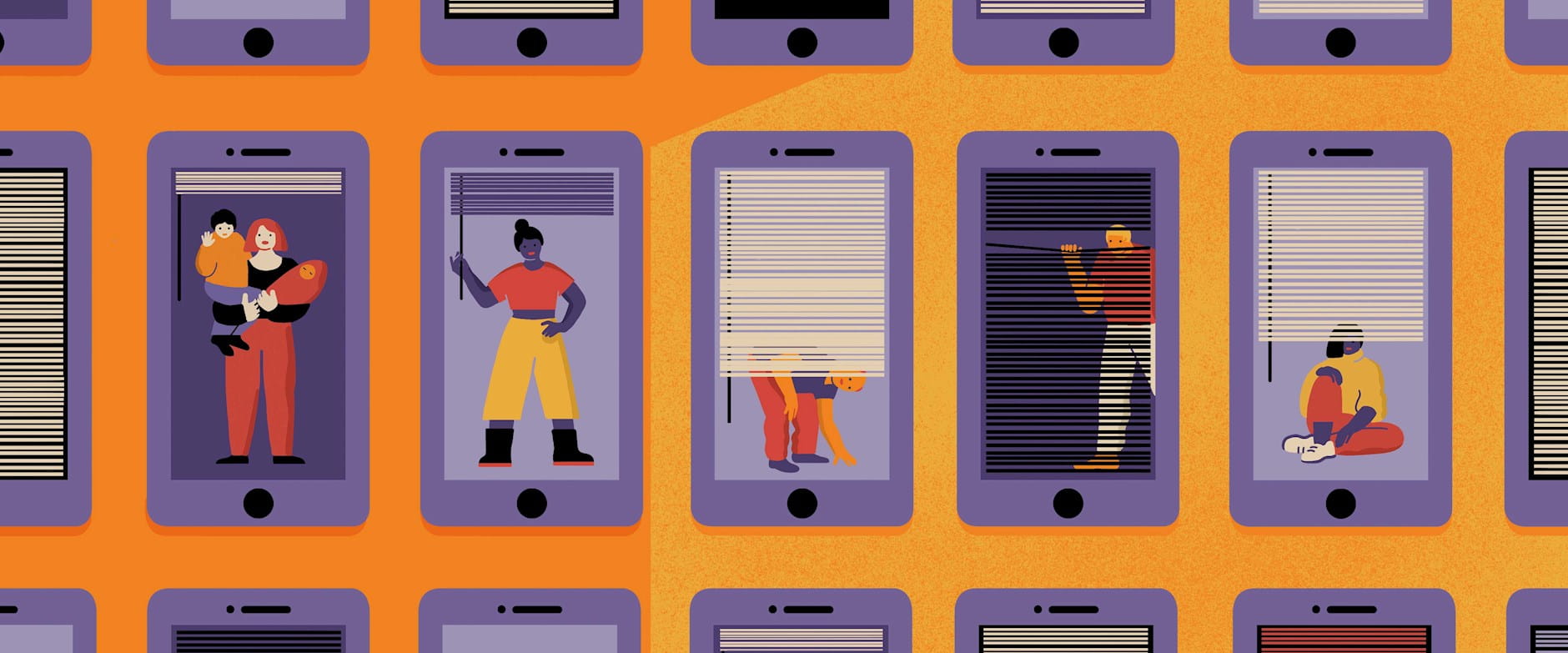

Facebook, Google, and dozens of other internet giants make billions off various slices of people’s personal data. For the most part, they provide you services in exchange for your data, without paying a cent. But if you could charge, how much would you want?

Boston University’s Tesary Lin and Chicago Booth’s Avner Strulov-Shlain looked into this question in experiments involving 5,000 Facebook users. The answers depend on the kinds of data in question, how you’re asked for them, and who you are, the researchers find.

“Websites use a combination of tactics, including different defaults, ‘nudging,’ and even obfuscation to get users to give up their data,” Strulov-Shlain says. “We wanted to see how users innately value their data, how the architecture of the choice presentation may affect users’ decisions, and whether some people are more susceptible to these differences than others.”

Since 2018, the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation has required websites to alert users before collecting personal data so that people can opt out. Websites handle this in various ways, sometimes making it easy to “reject all cookies” and sometimes requiring a user to do some extra digging and clicking to get there.

How this framing of the permission question affects our decisions—and even how we value our data in the moment—hasn’t been clear. Lin and Strulov-Shlain asked participants what prices they would place on various types of personal data connected to Facebook, including biographical data, that about friends and followers, and information from posts and likes. In the study, they varied how choices were presented, sometimes making opting in (or out) the default and at times providing price ranges suggesting how much value participants may place on their data.

The researchers report three key findings. The first is that when given free rein, participants placed wildly different values on their data—from $0 to infinity—but they generally assigned the same order of importance to the categories. Data about friends and followers were worth the most, while information from posts and the “about me” section was worth the least.

The research suggests that website sharing defaults that automatically opt in users oversample people who place a low value on their data, creating a bias in the numbers. But requiring users to opt in reduces this bias without a large decrease in the amount of data collected.

The way the question was framed made a big difference in how participants valued their data, the researchers find. For instance, a low price range of $0 to $50 reduced average valuations by 50 percent compared with a high range of $50 to $100. Meanwhile, when participants had to opt-in to share their data, their valuations increased by as much as 20 percent compared with an opt-out default.

And some participants were more susceptible than others to framing effects. “People who were younger, less educated, and lower income had lower baseline value for their data and were more affected by framing,” Strulov-Shlain says. “This creates a bias in data collection, where consumer groups who value their data less to begin with even more readily give it up once certain framing is applied.”

Thus, the findings about framing lead to a larger observation about choice architecture. Companies may want to gather as much information as possible, but data quality is crucial, emphasize Lin and Strulov-Shlain, writing that “biased input data often leads to biased insights and decision-making.” They give the example of Amazon, which tried but then abandoned a hiring tool after reportedly discovering that it had been trained on a biased data set that overrepresented men. The tool then was biased against female applicants, Reuters reported. To make accurate predictions, researchers and companies need to take pains to gather high-quality, unbiased data.

“With sampling, there’s always this tension between how many and who am I capturing. In our experiment, we find that more doesn’t necessarily mean better—how you ask your questions matters,” says Strulov-Shlain.

Companies, he notes, should keep that in mind when designing data-gathering strategies. And for the rest of us, remember that how the cookies pop-up asks for your permission may affect how you value your data at that moment.

Tesary Lin and Avner Strulov-Shlain, “Choice Architecture, Privacy Valuations, and Selection Bias in Consumer Data,” Working Paper, August 2023.

Let the events of your life enrich, not bias, your thinking.

Look Beyond Your Own Experience

Cash is only an effective incentive for certain types of tasks.

Money Can Inspire Effort More Easily than Insight

Trying to spare someone else’s feelings can leave the person feeling insulted.

Why Posting about That Promotion Is Better than Keeping QuietYour Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.