What Do We Get Wrong About Impact Investing?

Chicago Booth’s Priya Parrish explains what the critics miss about impact investing.

What Do We Get Wrong About Impact Investing?

Many of a business’ stakeholders—its customers, employees, and shareholders, for instance—may advocate for it to make decisions with something other than the profit motive in mind. But does this include decisions in response to geopolitics? And how would the cost of cutting ties with a company whose actions they disapproved of affect the choices of these various stakeholders?

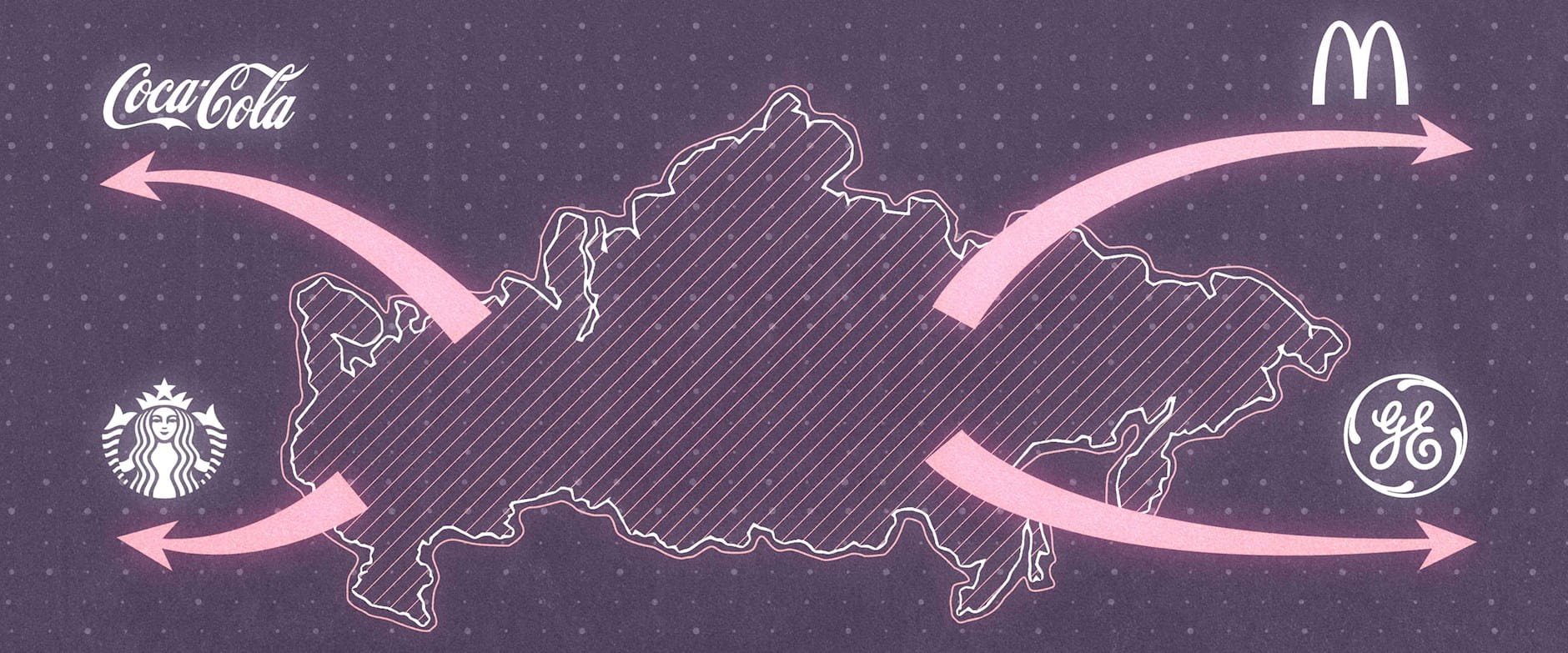

Chicago Booth’s Luigi Zingales, Harvard’s Oliver Hart, and MIT’s David Thesmar explored people’s willingness to demand “private sanctions” during the early months of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, when many Western-based international companies felt pressure to leave Russia.

Narrator: In the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in late February 2022, Western governments imposed harsh sanctions on Russia. According to Yale researchers, more than 1,000 businesses left the country in protest, leaving 1 million Russians without a job. Even the fast-food chain McDonald’s decided it was time to leave the country. The situation raises the question of just how much are customers, employees, and shareholders willing to give up for a cause?

Luigi Zingales: We experience every day now what some people call woke capitalism or the fact that companies seem to be taking moral stands on values issues. And so the question is, what is the legitimacy of this moral stand? Where does it come from? And at the end of the day, who pays for it, because it’s easy to be generous with somebody else’s money. But the question is, are you willing to be generous with your own money?

Narrator: That’s Chicago Booth professor Luigi Zingales. He and fellow researchers surveyed 3,000 Americans in May 2022, three months after the invasion. Respondents were assigned as either a shareholder, an employee, or a customer of a company that continued doing business with Russia. They found that two-thirds would cut ties with the company by selling shares, quitting, or shopping elsewhere. That figure fell to 53 percent when participants were told that such actions would cost them $100 personally. It then fell to 43 percent when the cost rose to $500. When the factor of personal cost was removed from the equation, 61 percent said private businesses should stop all commerce with Russia whatever the consequences. Just 37 percent said the decision should reflect only the economic costs and benefits of such an action. These opinions held steady for the customer and employee groups, but the shareholder group was more likely to sever ties with Russia if they thought it would have an actual impact. However, the researchers emphasize the importance of understanding whether people support these actions because they have a concrete goal in mind, or because they want to disassociate themselves from the actions of a bad actor, like Russia.

Luigi Zingales: This is very important because I think very few people dispute that we don’t want to supply microchips to Russia that uses the microchips to produce a more lethal weapon. So that’s an easy one. But going back to McDonald’s, McDonald’s used to have a chain of outlets throughout Russia, and they decided to leave Russia with a large cost, $1.4 billion of cost when they left. It’s not even obvious if you think from a strategic point of view that this is the right thing to do because what are you trying to achieve? Hopefully we’re trying to achieve the end of the war in Ukraine. But if you are trying really to generate a resentment of the population against Putin, it’s not obvious that a big ban from the West would do it rather than a big ban from the West might actually have a counterproductive effect.

Narrator: The researchers suggest that customer views on morality have the power to influence major corporate decisions for better or worse than originally intended.

Luigi Zingales: Customers have an enormous amount of power because think about the millions of customers of McDonald’s. So if it is true now customers of McDonald’s number one are spread throughout the world, including Russia, so I don’t expect the Russians to feel the same way as Americans. So it’s not obvious that our survey represents the world, number one. Number two, the typical customer of McDonald’s is in a very particular socio-economic group. So again, it’s not obvious that our survey represents what the customers want, but with this caveat, if you take the responses of our survey and you apply to all the customers of McDonald’s, you have 20 million customers a day. So even if this were a year, you have 20 million people, each one on average willing to pay $200 to get out of Russia. That’s a lot of money. And that justifies very easily spending $1.4 billion to get out. So it is not that inconceivable that when CEOs make these decisions they maybe are trying to capture what the customers or the employees or the shareholders want.

Narrator: If corporate power can be so heavily influenced by customer power in the arena of geopolitics, then it could pose questionable outcomes for business-to-business relationships with customer bases that have opposing moralities.

Luigi Zingales: So if this trend continues, I think we should introduce a new form of business risk, which I call stakeholder business risk. Because imagine I am a social media company, and as a social media company, I need to have access to a pretty important supply of cloud storage. And there are basically three companies providing cloud storage these days: Amazon, Google, and IBM, and especially Amazon and Google, they’re both located in a part of the country that is very liberal. So the risk that the employees might say, “We don’t want to supply cloud space to this company,” becomes a business risk that as a social media company, I need to factor in advance. It’s not a problem that is easy to solve because I could say, OK, I write a breach clause when I get the supply from Amazon Cloud to say that “If Amazon Cloud were to interrupt this relationship without just cause, they have to pay me a bazillion dollars.” OK? But also how do you manage it is by sourcing yourself from companies that are less at risk of this disruption of supply. We may end up in a world in which we have a segmented supply chain. We have a blue supply chain and a red supply chain.

We are worried about the world de-globalizing with all the inefficiencies that this might generate. But in fact, we should be worried about even the United States de-globalizing and fragmenting into a blue economy and a red economy.

Narrator: Traditional economics would assume that companies would want to maximize profits in all situations, but the evidence points to the conclusion that the majority of Americans don’t necessarily want the companies they shop from, work for, or invest in to behave that way. But there is still risk even beyond losing money.

Luigi Zingales: If customers or employees have the wrong notion of what can be effective, they might not only not be helpful, but be counterproductive. So not surprisingly because I’m an economist, but I am much more in favor of a more consequentialist approach that you want to take a moral stand with this moral stand as a desirable outcome, certainly as an undesirable outcome is not the right thing to do. There is an expression in Latin, Fiat iustitia, pereat mundus, that says, “I want justice to be implemented, and if the world goes to hell, I don’t care.” That’s not my view of the world. But as I said, I’m an economist. Maybe a philosopher thinks differently.

Chicago Booth’s Priya Parrish explains what the critics miss about impact investing.

What Do We Get Wrong About Impact Investing?

A panel of economists considers the currency's impact after a quarter century.

Has the Euro Been a Success?

A variety of data from the Great Recession shows a significant reduction in death rates, partly because of less air pollution.

The Upside of Recessions: Cleaner AirYour Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.