Startups, Forget about the Technology

New ventures should focus all their efforts on problem-solving.

Startups, Forget about the TechnologyThe challenges of cleaning a bathroom are varied, unexpected, and fascinating. Before you skip to the next essay, give me a chance to explain.

A few years ago, I was doing some research for a large manufacturer of household cleaning supplies, in order to create innovations in bathroom cleaning. First, we convened several focus groups and interviewed participants about bathroom cleaning. The more we listened, the more problems and frustrations we heard. Many people didn't like the overpowering smell of the products used to clean washrooms. Many felt concerned about harsh chemicals, and that cleaning itself was difficult and time consuming. There were many other problems, not all of them appropriate for these pages. Suffice it to say that the focus groups generated a lot of issues.

After the focus groups wrapped up, we decided to do some field research and observed people cleaning their home bathrooms. We wanted to see and talk to people in that context. As expected, we saw some things that people had complained about in focus groups: the products were harsh, they burned people's hands—and were sometimes toxic in the air, plus the cleaning process could be long and challenging.

But we also started to notice some unusual things that hadn't come out in the group interviews, one of which was what you might call a home remedy or work-around. We saw people, on their own initiative, applying automobile wax to their bathtubs and shower tile. The label on the auto-wax product did not mention its applicability to bathroom cleaning, but when we asked people why they were using the wax, they mentioned several benefits. The wax made the tiles shine, as well as easier to wipe clean or rinse off.

The exercise was a healthy reminder of the power of design thinking, a term that is used and understood in different ways but that starts with people. They are the humans in human-centered design, the users in user-centered design, and the consumers in consumer-oriented design. Design thinking requires an in-depth understanding of people's needs, wants, problems, frustrations, and lives. And this necessitates some fieldwork to understand the challenges people face. In the case of the bathroom-cleaner research, if we hadn't gone into homes, observed people cleaning their bathrooms, and talked to them about the process, we might never have discovered their use of auto wax, or uncovered the unmet needs behind this behavior.

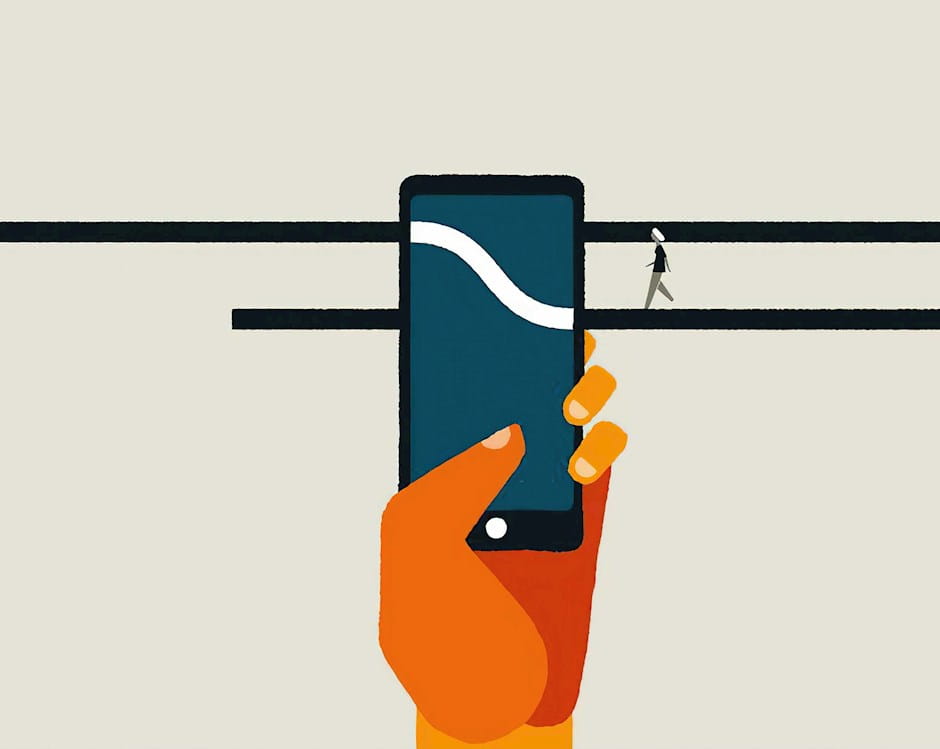

Although innovation begins with listening to customers, all too often, companies try to innovate backward: they first develop some new technology, and then try to turn it into a successful product. They start with a solution, and hope it might address a customer need. Ultimately, this process only succeeds if enough people will buy the product, and this “if you build it, they will come” approach is one reason so much technology goes uncommercialized.

Design thinking, as a way of innovating, rests on three pillars: desirability—focusing on the needs of people; feasibility—the possibilities of technology; and viability—the financial requirements for business success. It is a way of coming up with products and services that people actually want, are feasible from a technological standpoint, and are viable from a business perspective. The innovations at the intersection of these three pillars have the highest potential.

Because design thinking starts with people and focuses on creative problem-solving, it can be applied to a wide range of industries, products, and services. It has been successfully used by for-profit and not-for-profit institutions, by business-to-consumer and business-to-business companies, and for physical products as well as services.

People wanted a protective barrier on their shower tiles. Because the market for bathroom-cleaning supplies didn’t fill that need, they instead turned to a work-around.

The process is critical, and a core tenet is bringing together cross-functional expertise from start to finish. This approach was pioneered by IDEO, the firm that designed the first usable mouse, for Apple’s Lisa computer, in 1980. At that time, innovation was typically siloed. Someone in the research-and-development or the engineering department would come up with an idea and hand it off to someone in the design department, who would in turn hand it on to someone to build it, and then to somebody else to market and sell it. IDEO used an entirely different approach, however, bringing all these capabilities together at the same time. In doing this, it helped popularize the notion of cross-functional teams in which people across multiple disciplines, with distinct expertise, work together throughout the life cycle of a project. Design thinking depended on building teams that comprised researchers (including people with anthropology backgrounds), as well as people in strategy, R&D, marketing, manufacturing, industrial design, finance, and so on. While this approach is now more common, it is remarkable how many organizations still deploy something closer to the traditional siloed model.

A design-thinking approach proceeds along the following lines:

Once you’ve assembled a cross-functional team, the first step is really one of empathy. Just as it was in the bathroom-cleaning research, the goal is to learn about the people for whom you’re designing, to gain a deep understanding of their lives, needs, problems, and frustrations.

This stage begins by uncovering a lot of qualitative customer data, with the aim of defining meaningful problems to solve. Come up with core themes or insights, and then develop those insights into problem statements that can be used to spark ideas. Look for customer needs that are currently unmet or only partially met by existing products. Once you define customer problems, developing solutions can be much more targeted.

To identify those problems, it helps to have good questions, which typically start broad. When interviewing people about bathroom cleaners, we didn’t start by asking about cleaning products. Instead, we asked people about their lives and overall cleaning routines, and to show us what they actually did. The questions were less product specific and more journey or process specific. For example, we’d say, “Tell us about the last time you did this. What was the process you went through? What worked best? What was worst?” We eventually drilled down to “Why did you do that?” and “Show us the products you use, and how you clean your bathroom.”

This sort of in-context research process is standard practice for many innovative organizations today. For example, in his 2017 book Hit Refresh, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella observes, “The business we’re in at Microsoft is to meet the unmet, unarticulated needs of customers. That’s what innovation is all about. There’s no way you’re going to do that without having empathy and curiosity.”

It’s important to consider which end users will give you the most useful responses: people who are at the extremes are often more articulate about their needs. Say you are trying to create a new pet-care product. The best subjects might be people who own multiple pets, or people who run pet-walking or pet-sitting businesses. Tapping into groups such as these, that experience the problems in the extreme, is more likely to uncover unique insights and inspire novel innovations that could be relevant for the broader market. It’s not that you design solely for people with extreme needs; rather, people in the mainstream may not have developed the same language to express their needs. In the cleaning-products example, extreme users included people with very large families, those with allergies to harsh chemicals, people who clean very frequently or very infrequently, and people with brand-new versus very old bathrooms.

If the first phase of design thinking is about building empathy to inspire innovation, the second is about creating new ideas. Because you’ve been immersed in the end consumers and their needs, you’re able to come up with more-effective solutions, and to do so efficiently.

Take my bathroom-cleaner example. There was a clear need that wasn’t being met: people wanted a protective barrier on their shower tiles to reduce the cleaning effort. Because the market for bathroom-cleaning supplies didn’t fill that need, they instead turned to a work-around by using a product designed for cars. Through interviews, we realized people were willing to take an extra step up front to avoid a future pain, to invest more time initially in applying a car wax to avoid a greater amount of time, energy, and effort later. They wanted to make future cleaning easier, therefore they wanted something that would prevent soap scum, mold, and mildew from sticking to the tile. When you clearly identify the problem, you know what you need to solve.

Ultimately, the evaluation process should essentially lead us back into the bathroom, to ask the customers which of the solutions we’ve come up with best meets their needs.

In terms of effective ideation, more than 50 years of research on the subject has demonstrated that traditional, in-person group brainstorming suffers from significant flaws. Research by Radford University’s Gary R. Schirr on ideation suggests that in-person group brainstorming tends to hinder both the quality and quantity of ideas. In a group setting, not everybody is fully engaged. Only one person can share his or her ideas at a time, which at least temporarily blocks everyone else from sharing their ideas. A third problem is conformity: when we hear others’ ideas, we’re influenced by them, tend to conform to them, and generate more ideas like them.

A different approach, modeled on research by Columbia’s Olivier Toubia, is to start generating ideas first as individuals, before using the power of the group. Individual and group brainstorming can then come together using a simple online discussion-board format, where individuals anonymously post their own ideas, and then other group members build upon those ideas. This can help keep separate the process of generating ideas from that of evaluating them, which is an important distinction. One advantage of using an online method is that people can contribute in their own time, rather than having to be together in the same room at the same time. Another is that their comments can be kept anonymous, eliminating any bias toward ideas that come from senior executives. Toubia’s research suggests this approach is more effective than traditional in-person group brainstorming and generates a higher quantity and quality of ideas.

Ultimately, the evaluation process should essentially lead us back into the bathroom, to ask the customers which of the solutions we’ve come up with best meets their needs. The final step of design thinking is to continue to deepen our understanding of the need, and to test and refine initial solutions. It’s important to assume up front that you don’t have the ideal solution, so it will be necessary to test and iterate, retest and reiterate, and learn along the way.

The team creates prototypes of the most promising ideas, and then tests these with users to get their feedback and to refine the prototypes. A prototype is part of a feedback loop that helps us understand the problem more in-depth, to ensure our solutions are appropriate.

The simplest prototype is a new product description and visual, what some people call paper prototypes, that you can take to customers for feedback. What do they like and dislike about the product? How might they improve it? How likely would they be to buy it? After this stage, you can move to testing physical prototypes that may or may not be functional. You’re looking for quick feedback to refine the idea and test it again, without investing a lot of time and money. This stage is ultimately about failing and adapting. Expect to fail along the way—fail fast, fail cheaply, learn, and figure out the next best thing to do.

The most promising prototypes will move forward into development, and eventually one will launch as a product or service that meets the three tests of design thinking: it is desired by customers, technically feasible, and viable from a business standpoint.

This may all sound very linear, as if the process simply moves from one stage to the next. But design thinking is messier than that. It’s a process of repeated divergence and convergence: the empathy phase uncovers diverse needs, and teams diverge on what’s important until they converge on a few key themes. They diverge again at the ideation stage, coming up with a variety of ways to solve the problem that’s been identified, until they converge on a small set of high-potential solutions. Also, design thinking is flexible and agile, so teams move back and forth rather than only in one direction. You might test a few prototypes and learn that some just don’t work, which would prompt you to go back and ideate more. You’d then develop more prototypes, test those, and perhaps repeat the cycle. The result is an iterative approach to innovation.

Design thinking eventually led to recommending a new bathroom-cleaning product: a daily shower cleaner. This now-well-known product comes in a spray bottle and quickly creates the barrier consumers sought for keeping mold, mildew, and soap scum from sticking to shower tile. The success of the daily shower cleaner is one example of the power of design thinking. Meet customers in the environment in which they use the product, ask good questions, listen and observe closely, and iterate solutions to solve important, unmet customer needs. The organizations that do this will innovate more systematically, and have higher success rates.

Arthur Middlebrooks is clinical professor of marketing at Chicago Booth and executive director of Booth’s Kilts Center for Marketing. This essay is adapted from a presentation delivered at the Kilts Center’s Marketing Summit 2019.

Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.