The Winner’s Dilemma in ‘Liar’s Poker’

What a seminal book about Wall Street says about morals and moneymaking.

The Winner’s Dilemma in ‘Liar’s Poker’

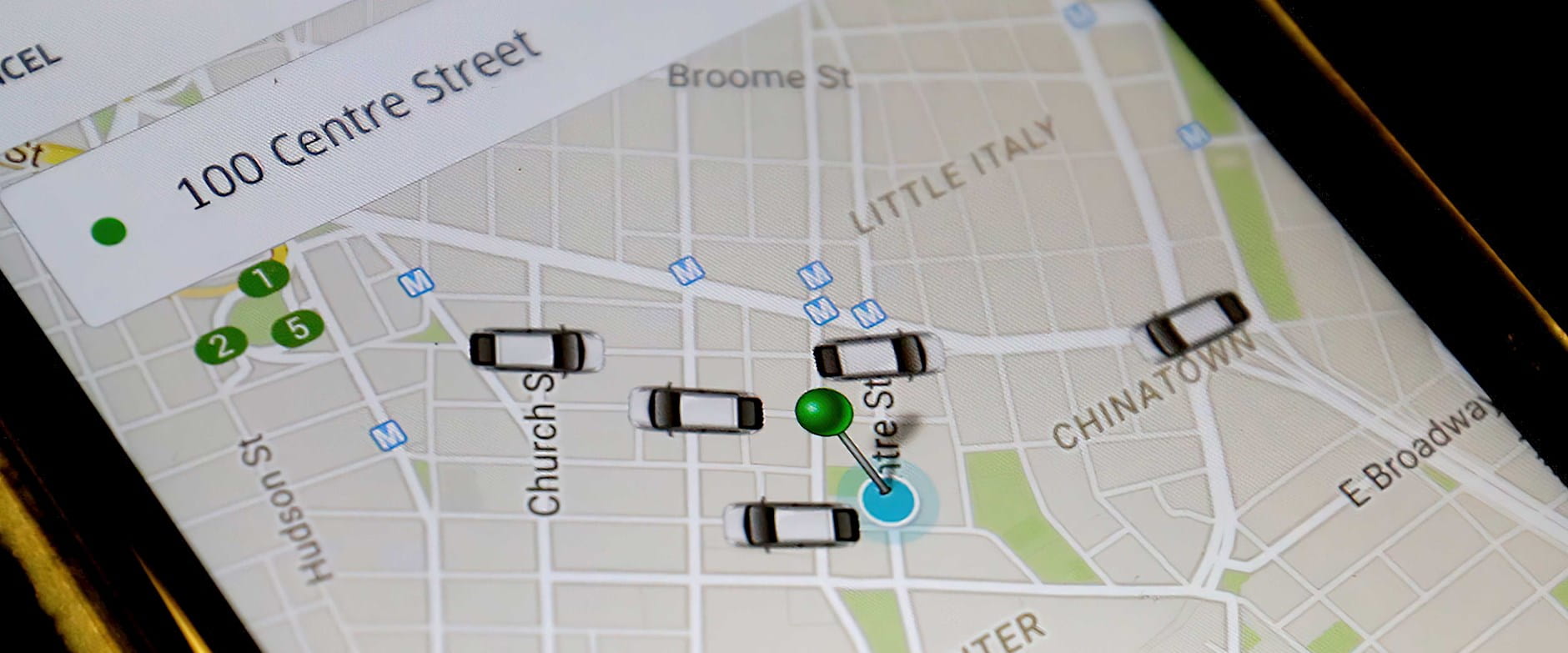

Minute control of employees’ workplace activities has been a goal of some managers and management scholars for more than 100 years. But actually exercising such control is a difficult proposition: unmotivated employees do poor work, money alone has limited motivational power, and non-pecuniary motivational efforts are generally clumsy and transparent. But with more and more people working “gig economy” jobs mediated through an app, Chicago Booth’s John Paul Rollert considers whether contemporary companies can combine behavioral insights with enormous amounts of data to more effectively guide the actions of their labor forces.

John Paul Rollert: Human beings, they’re kind of annoying, aren’t they? Making their own choices, doing the things they want to do, the way they want to do them (scoffs), on their own timetables. Most times, they don’t even ask you for your opinion, as if you didn’t have any say in the matter. Sheesh!

(points to a photo of Kim Jong-un) I bet this guy doesn’t have that problem. People listen to everything he says. They do just want he wants, when he wants, the way he wants. Poohoo! Supreme leader, I guess that’s the price of living in a free society. Whatever.

So what do you do about people? Especially the people who work for you: your employees, the people you manage. You know what you want them to do; you probably know the way you want them to do it. But how do you get them, well, to cooperate? To follow orders—and not being fussy or dragging their feet, but to be happy about it? Almost like they were your own very puppet. And you were their Geppetto.

Solving this problem was the life’s work of this man (points to a black-and-white photo): Frederick Winslow Taylor. Taylor was a business professor, a mechanical engineer, and a man unafraid to sport wing-tip collars. He was also a key figure in what was known as the efficiency movement, an effort at the beginning of the 20th century to reduce waste and improve economic growth by implementing practices that would streamline industrial production. Taylor’s most important contribution is this book (pointing to a picture of a textbook), The Principles of Scientific Management, a work that is now regarded as the foundational text of management consulting.

As Taylor says in the book, “The responsibility of a good manager is to make a study of how different tasks in the workplace should be done.” The goal, he said, is to create “many rules, laws, and formulae, which replace the judgment of the individual workman.” But that’s not all. It wasn’t only that scientific management aimed to rid workers of the pesky need of having to figure out things for themselves; they didn’t even need to know why they were doing what they were doing. They merely needed to do what they were told, for the science of management could only succeed if workers followed instructions with—and these are Taylor’s words—“absolute uniformity.”

Fair enough, but saying you want absolute uniformity in the execution of some task and getting it are two very different things. When I was a child, my mother was very clear she wanted absolute uniformity when I made my bed in the morning. But that didn’t mean that little John Paul ever mastered the art of hospital corners. Taylor knew this, which is why he talked a lot about monetary incentives. He knew that few people swooned at the idea of making 71 and 1/3 widgets each day. But if you offer them enough money for their efforts, they might just undertake them with something that approximates absolute uniformity. Still, this was something of a last best option: if people only did what you wanted them to do because you were paying them money, they tended to be half-hearted in their efforts. And if you didn’t watch them closely, chances are they would try to cheat the system.

Accordingly, a central part of the science of the workplace was to bring about what Taylor called “a complete change in the mental attitude of employees.” “Managers,” he said, “needed to understand the motives which influence men and to harness them in favor of the work at hand.” Another way of putting this is that if money is an exterior motivation, the science of the workplace could only be perfected when the need to get the job done was in here. The drive had to come from within. Now, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that so much of the study of management throughout the 20th century involved finding new ways of motivating workers beyond simply giving them more money.

If you’ve ever worn a 10-gallon hat to the office, done a trust fall with your boss, or sung “Rocket Man” on a work cruise, you’ve engaged in some of the clumsier attempts to create that sense of inner motivation, that buzz buzz that makes you a happy little worker bee. Now, we can all laugh at these efforts, in part because they’re a little ridiculous. But also because they’re patently obvious. We know what our bosses are doing to us, and oftentimes, we are willing collaborators. But what about attempts to motivate us that are little less obvious, that go on without our even being aware of it?

Take the case of Uber. As Noam Scheiber of the New York Times has reported, in the last few years, the ride-sharing service has drawn on the insights of behavioral science and video-game technology to solve the problem of getting drivers to drive whenever they need them on the road, this notwithstanding the fact that a central part of Uber’s pitch is that drivers can work on their own schedules. For example, as Scheiber reports, Uber tweaked the algorithm on the app drivers use to automatically queue up new rides before the current ones have finished.

The behavioral insight is the same one that streaming services rely on. For just as Netflix knows that no sane person decides to spend a Sunday afternoon watching 11 episodes of Sabrina the Teenage Witch, if the Uber app is always prompting you to do just one more pickup, you’ll quickly find yourself binge driving. Another change Uber made is to take advantage of the human affinity for goal setting. The app was redesigned to constantly update drivers on how close they are to reaching certain arbitrary sums, or to matching the number of rides they’ve done the previous weeks. At the time, drivers are also given a steady stream of encouragement from real-time feedback, to badges they can earn from passengers, to virtual pats on the back from Uber high command. The insight is simple: a few words of encouragement can be a powerful motivator to keep us working hard—even when they come from the disembodied voice of some distant authority. (speaks to someone off-screen) Right boss?

Boss: You bet, John Paul!

John Paul Rollert: Gee, thanks.

Boss: Just one more minute now.

John Paul Rollert: (responds to boss) You got it.

Now, to be sure, businesses have been using these kinds of tricks for decades. But with technology that now allows us not only to gather and assess fine-grained data on the performance of each and every worker, but to use that data to tailor the encouragement we give them, we are increasingly able to ensure the goal of absolute uniformity. Companies are able to get what they want from their employees the way they want it, without ever having to look over their shoulders.

Make no mistake. This is what the future of work looks like. With continuing technological developments, advanced insights into behavioral science, and the capacity to harbor and deploy big data in the years to come, the ability of companies to shape the activity of the workplace in favor of efficiency and productivity will only continue to grow. They will only become more proficient in assembling the strings that will make you their Pinocchio. Now, of course, this was the dream of Frederick Winslow Taylor, the high priest of scientific management. But should it be yours? That may depend on how much you value free will and individual agency—or maybe where you think you’ll end up in the company hierarchy. Will you be acting with absolute uniformity according to the wishes of some supreme leader? Or do you think you’ll effectively be one?

What a seminal book about Wall Street says about morals and moneymaking.

The Winner’s Dilemma in ‘Liar’s Poker’

You can’t fix all the world’s problems, so pick your battles.

What a Hot Dog Taught Me about Ethical Priorities

Chicago Booth faculty field questions from Booth students and alumni about how COVID-19 has changed, and will change, various aspects of management and leadership.

How Will COVID-19 Change Management and Leadership?

The prestigious award from the American Finance Association recognizes top academics whose research has made a lasting impact on the finance field.

Example Article Swiss

At the Kilts Center’s annual Case Competition, a student team leveraged LLMs to create innovative product solutions for Microsoft.

Example Article Swiss

The Booth dean and professor (1939–2024) was an expert in microeconomics, strategy, and industrial organization and served in the US government.

Example Article SwissYour Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.