US Banks’ Big Interest Rate Gamble

Over a decade after the 2008–09 financial crisis, institutions were still privatizing gains and socializing losses.

US Banks’ Big Interest Rate Gamble

Sebastien Thibault

When policy makers around the world want to influence their constituents’ behavior, they have a few options. They can offer a carrot, such as a tax incentive, stipend, or other reward. They can use the legislative stick by passing a mandate or a ban.

But research suggests they should turn more often to a third tool, a “nudge,” which in many cases is the most cost-effective option.

Nudging is the word used in behavioral science for structuring policies and programs in ways that encourage, but don’t compel, particular choices. For instance, requiring people to opt out of rather than into a program, such as a retirement savings plan, might nudge them toward participating. So might reducing the paperwork necessary to enroll.

Policymakers have seen opportunity in nudging, which is why the United States has a White House Social and Behavioral Sciences Team devoted to nudging, and other governments have analogous teams. But a group of researchers—UCLA’s Shlomo Benartzi, Harvard’s John Beshears and Cass R. Sunstein, University of Pennsylvania’s Katherine L. Milkman, Chicago Booth’s Richard H. Thaler, Maya Shankar of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, Will Tucker-Ray and William J. Congdon of ideas42, and Steven Galing of the US Department of Defense—examined the costs and efficacy of various intervention types to assess whether nudges are an effective use of public resources.

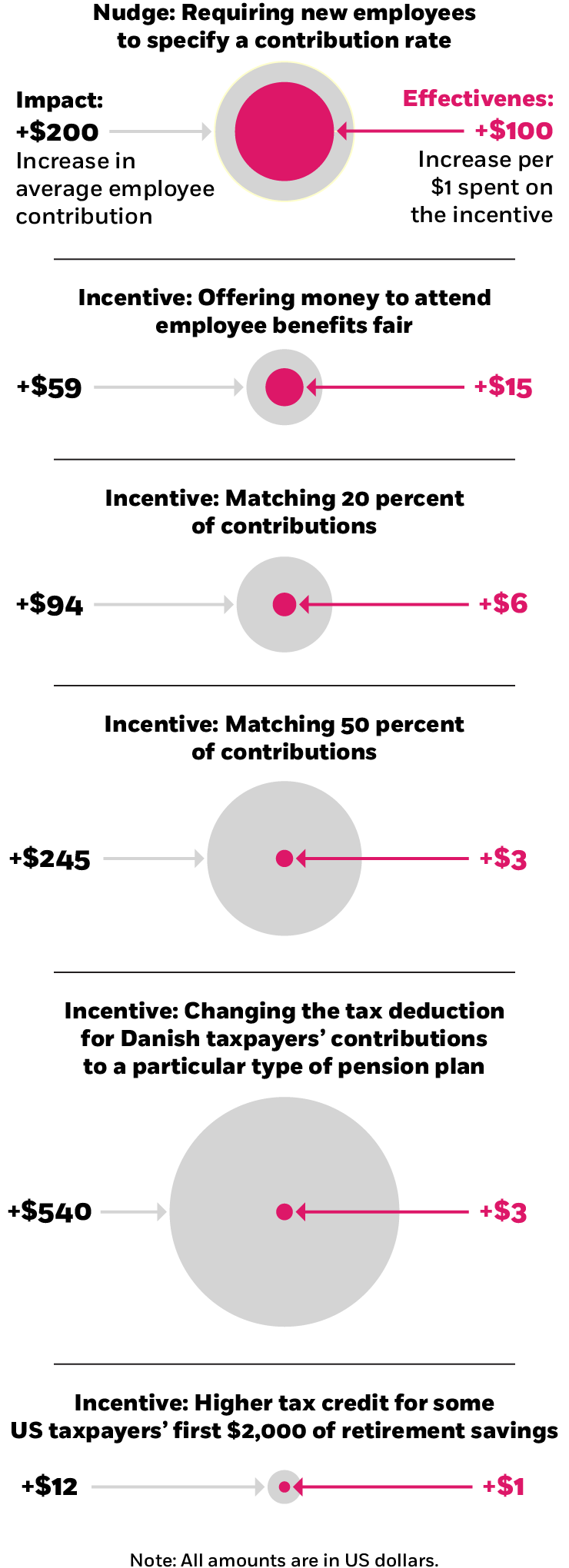

Cost-effective way to entice people to save more for retirement

Assessing a range of incentives to encourage people to contribute more to retirement savings plans, the researchers find a nudging approach sees strong results for every US dollar spent.

Benartzi et al., 2017

The researchers focused on four behavioral outcomes identified as priorities by the US and UK governments: increasing retirement savings, college enrollment, energy conservation, and flu vaccinations. They used existing research into specific interventions—some undertaken by lawmakers, others by companies in the private sector—to assess the respective costs and results.

In one case, the researchers looked at a nudge by the tax-preparation firm H&R Block, which offered clients assistance in filing college financial-aid paperwork, and compared that approach with subsidies and tax incentives offered at the state and federal levels. The nudge produced 1.5 additional college enrollees per $1,000 spent—making it 40 times more effective than the next most effective intervention the researchers analyzed.

Likewise, nudging turned out to be the most cost-effective way of encouraging energy conservation. One program to nudge consumers into lower electricity use, sending letters comparing a household’s energy consumption to that of its neighbors, saved 27 kilowatt-hours per dollar spent. In contrast, a rebate offered by California utility companies produced savings of only 3.4 kWh per dollar, and other demand-management policies that relied on a combination of consumer education and monetary incentives averaged 14 kWh per dollar.

The findings suggest that nudges offered the most impact per dollar for each of the other two policy goals as well. “Our selective but systematic calculations indicate that the impact of nudges is often greater, on a cost-adjusted basis, than that of traditional tools,” write the researchers. “In light of growing evidence of [nudging’s] relative effectiveness, we believe that policy makers should nudge more.”

Shlomo Benartzi, John Beshears, Katherine L. Milkman, Cass R. Sunstein, Richard H. Thaler, Maya Shankar, Will Tucker-Ray, William J. Congdon, and Steven Galing, “Should Governments Invest More in Nudging?” Psychological Science, May 2017.

Over a decade after the 2008–09 financial crisis, institutions were still privatizing gains and socializing losses.

US Banks’ Big Interest Rate Gamble

Chicago Booth’s Jean-Pierre Dubé explains how retailers use hidden fees to obfuscate prices and avoid transparency.

Hidden Fees, Drip Pricing, and Shrinkflation

Chicago Booth’s Raghuram G. Rajan describes the task ahead for the US Federal Reserve.

Why a Soft Landing Is So HardYour Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.