How Can Discount Brands Stay Discounted?

During tough times, more Americans buy house brands, driving up prices faster than for national brands.

How Can Discount Brands Stay Discounted?

Tiago Galo

New product launches are fraught with danger. Aside from facing potential manufacturing, logistics, and marketing flops, companies risk losing millions of dollars if what is expected to be a hit disappoints.

In recent years, businesses have been tapping the internet to cheaply and simply survey a large base of potential customers. This “crowdvoting”—a spin on crowdfunding and crowdsourcing—allows companies to ask self-selected website visitors to vote on which prospective new products they would buy.

But while asking your customers’ opinions might seem simple and straightforward, crowdvoting requires astute decision making by market researchers, according to Victor Araman of the American University of Beirut and Chicago Booth’s René Caldentey. Among other things, the voting process can take time, a consideration companies have to weigh against the appeal of getting quickly to market.

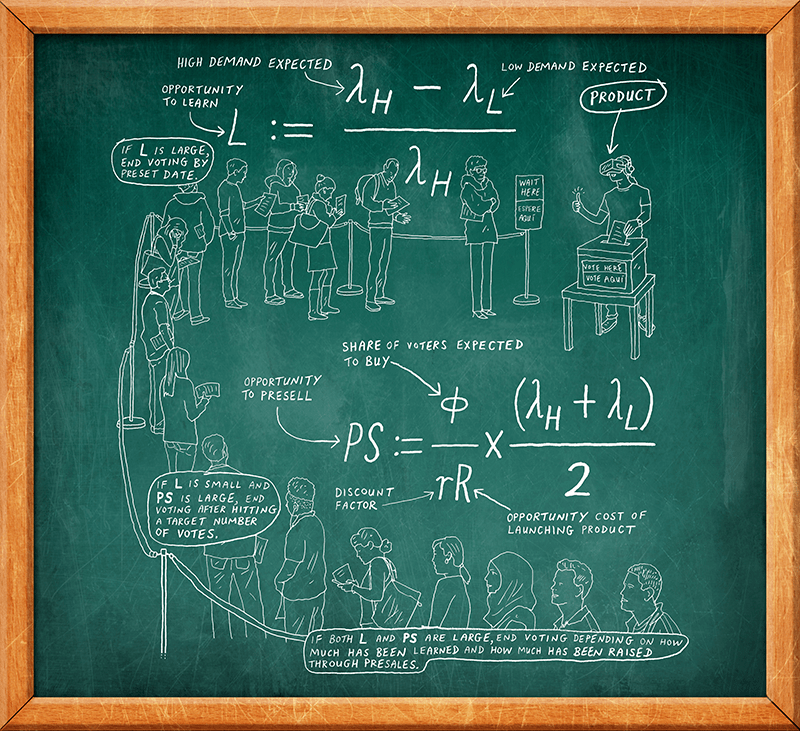

Araman and Caldentey developed a model to help businesses choose when to end a crowdvoting campaign. For many companies, this means closing the polls either by a certain date or at a set number of votes. But the model—which takes into account that some crowdvoting systems get into crowdfunding territory, allowing voters to essentially vote by preordering products—suggests that a rolling target based on a variety of factors can help some businesses pinpoint the optimal time to launch, or abandon, a product.

Some companies may already have a strong sense of how many people might buy a new product, or may be looking for confirmation of what they think they know. Others may be accepting preorders, to raise cash to fund the product launch. The researchers conclude that these are the companies that would do well to end a voting period after receiving a set number of votes (or orders).

If voting signals diminishing risk that the product will flop, delay reduces immediate revenue potential.

For other companies, waiting to gather a certain number of votes can lead to lost opportunities as potential revenue is delayed. This can be the case when a company’s management has little idea of potential demand and no plan to offer advance sales—or suspects that people who vote for a product might not actually buy it. In this situation, a business would be wise to set an end date for voting.

There are also cases in which demand is unclear but opportunities for preselling are high. Oculus VR, a virtual-reality-headset maker, used the crowdfunding platform Kickstarter early in its life, collecting votes in the form of preorders at $300 or more. Over the course of one month (August 2012), the company raised almost $2.5 million from 9,522 people, 10 times its goal. Facebook acquired Oculus in 2014.

The Equation: How to design a crowdvoting campaign

Oculus set a deadline for voters. The researchers didn’t study that or any case in particular, but their model suggests that a dynamic stopping rule determined by factors that change as the polling progresses can significantly increase crowdvoting’s effectiveness in certain scenarios, such as the one Oculus faced. For example, as votes accumulate, they may push up or down the company’s expectations of a product’s market potential. This in turn might change the date, or vote tally, at which it makes sense to cease voting and launch the product. If voting signals diminishing risk that the product will flop, delay reduces immediate revenue potential. Accounting for different levels of risk yields different recommendations.

On the other hand, relying on a fixed date or number of votes may lead a company that’s trying to decide if and when to launch a product to make a decision either too soon, diminishing preselling opportunities and reducing the ability to forecast market potential, or too late, needlessly delaying the product launch and revenues that come with it and increasing the chances that customers will forget to buy the product they’d voted for weeks or months earlier.

Victor Araman and René Caldentey, “Crowdvoting the Timing of New Product Introduction,” Working paper, January 2016.

During tough times, more Americans buy house brands, driving up prices faster than for national brands.

How Can Discount Brands Stay Discounted?

Exploiting customers through discounted, auto-renewing promotional offers can backfire.

Why Locking In Subscribers Is Bad for Business

Television advertising may be considerably less effective than published studies suggest.

Why the Power of TV Advertising Has Been OverstatedYour Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.