Capitalisn’t: Why This Nobel Economist Thinks Bitcoin Is Going to Zero

Chicago Booth’s Eugene F. Fama explains his skepticism about the world’s biggest cryptocurrency.

Capitalisn’t: Why This Nobel Economist Thinks Bitcoin Is Going to Zero

This website uses cookies to ensure the best user experience.

Privacy & Cookies Notice

|

NECESSARY COOKIES These cookies are essential to enable the services to provide the requested feature, such as remembering you have logged in. |

ALWAYS ACTIVE |

| Reject | Accept | |

|

PERFORMANCE AND ANALYTIC COOKIES These cookies are used to collect information on how users interact with Chicago Booth websites allowing us to improve the user experience and optimize our site where needed based on these interactions. All information these cookies collect is aggregated and therefore anonymous. |

|

|

FUNCTIONAL COOKIES These cookies enable the website to provide enhanced functionality and personalization. They may be set by third-party providers whose services we have added to our pages or by us. |

|

|

TARGETING OR ADVERTISING COOKIES These cookies collect information about your browsing habits to make advertising relevant to you and your interests. The cookies will remember the website you have visited, and this information is shared with other parties such as advertising technology service providers and advertisers. |

|

|

SOCIAL MEDIA COOKIES These cookies are used when you share information using a social media sharing button or “like” button on our websites, or you link your account or engage with our content on or through a social media site. The social network will record that you have done this. This information may be linked to targeting/advertising activities. |

|

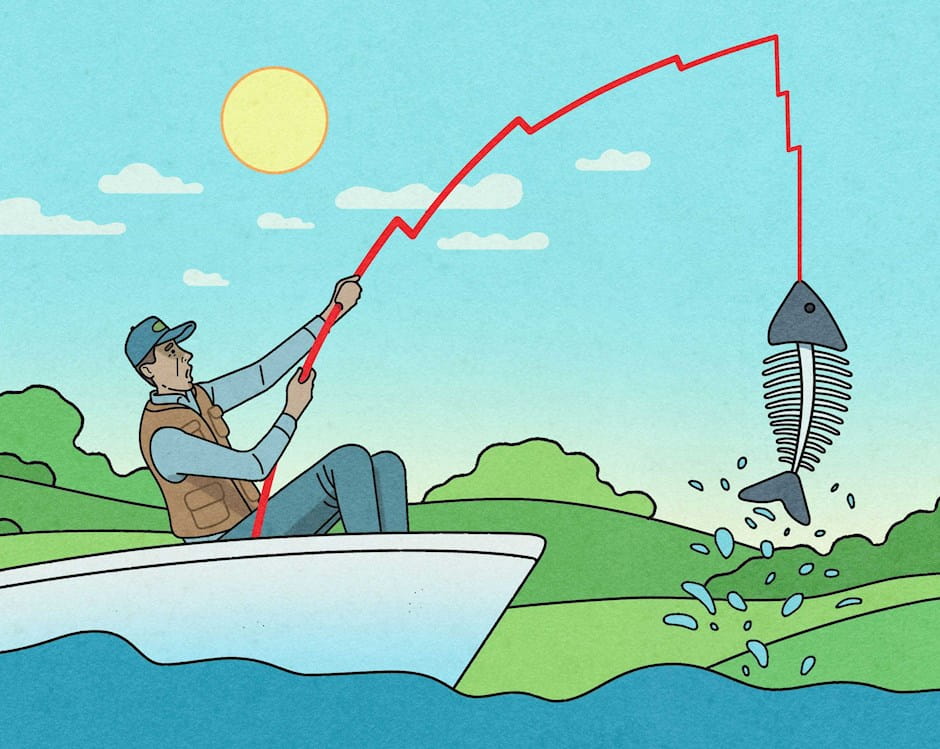

Pete Ryan

Researchers across disciplines have pieced together a timeline of cognitive costs.

Six Ways a Tough Choice Can Tax Your MindHal Weitzman: Would you work if you weren't being paid for it? Social media is full of people criticizing companies for exploiting interns and prospective hires by underpaying or not paying them at all. Is that a universal feeling, or does it reflect Western values and attitudes that aren't replicated elsewhere in the world?

Welcome to the Chicago Booth Review Podcast, where we bring you ground-breaking academic research in a clear and straightforward way. I'm Hal Weitzman, and today I'm talking with Chicago Booth's, Thomas Talhelm, about his research on what motivates people around the world to work.

Thomas Talhelm, welcome back to the Chicago Booth Review Podcast.

Thomas Talhelm: Yeah, thanks for having me.

Hal Weitzman: We are here to talk about your research about what makes us work. Why do we work you? You've said that this project started as what you call dumpster diving. What dumpster were you diving into and why?

Thomas Talhelm: Yeah, so in the winter quarter at Booth, we will have these faculty research meetings, and it's about research and progress. And so people will present projects to get feedback. And my colleague, Devin Pope, who's a behavioral economist, was presenting on his research on a study that he had done.

And what he had done is he gave a really simple, work is maybe even stretching it, but we'll call it a work task, gave a simple task to 10,000 people on a platform called MTurk. This is run by Amazon. People post tasks there, companies do it, researchers do it as well. He gave a task to 10,000 people. He asked them to push the A and B buttons on their keyboard as many times as they could for 10 minutes. And then he gave people, he randomized people to all sorts of different setups, framings, incentives, to try to get them to push the buttons harder. And so it's just like a mega study.

Some of those versions were you give people money, so if you push every thousand times you push the buttons, I'll pay you a certain amount of money extra. Other versions were just what you might call nudges, so just saying things like, most people try really hard and push the buttons 5,000 times. And so it's suggesting a social norm.

And across the board, lots of these different interventions were successful. But the money won on every occasion. I mean, just paying people more money always outperformed the social nudges, things like social comparison. There was a version that the researchers just said, "Please try hard." And that actually worked. The people did try a little bit harder when you said, "Please try hard," but the money, so paying people for their performance, always outperformed any sort of psychological social nudge.

And so Devin was presenting this and I said, "Wait a second. You ran this on MTurk, this platform. Most of the participants are in the United States, but actually the second-largest country is India. Did you look at the India data?" He said, "No, I just analyzed everybody together." "Do you want to look at the India data?" "No." "Are you interested in culture?" "No." "Can I have the data?" "Sure."

And so he just sent me his data. And I started looking around in his data just thinking, well, what if we split out that study and look at the people from the US and the people in India? And when I was looking through his data, that's where I found the hints that led to all these separate studies. But yeah, I mean dumpster diving in the sense that Devin was like, well, I don't need this data anymore and I don't really care about your question, so have at it.

Hal Weitzman: So you're the guy who goes through the recycling bins looking for new experiments to do?

Thomas Talhelm: That's exactly it.

Hal Weitzman: And in this case, you found one. Okay.

So your paper has this great title. The Homo Economicus Model of Work Describes Men More than Women, But Only in WEIRD Cultures. There's a lot there. Reminds us, first of all, or explain to us what the Homo Economicus model of work means.

Thomas Talhelm: Yeah. So the Homo Economicus model is this idea from classical economics, the idea that people should be self-interested, and that they should be rational, calculating their payoffs for the things that they're doing. And if it's something social, but that's not benefiting me economically, if I'm not making money off of this, it doesn't serve my purpose, then I shouldn't do it. And if it's benefiting somebody else and I'm not benefiting, then I also shouldn't care.

Now, obviously this is a simplified model. It's not that economists think that humans are a hundred percent really like this. Psychologists have been dumping on this model for years and years, and economists definitely agree that it's just a model. It's not actually saying that people are a hundred percent this way, but that's the Homo Economicus model.

In the paper, I contrast it with what I call homo psychologists, which is the idea that humans, in addition to being selfish and wanting to make money, also care about things like their reputation, how other people feel, if you give me a gift, I'm not obliged to give you a gift, but I'm a human, I feel like I kind of owe you something. So that's the psychologist [inaudible 00:05:29]-

Hal Weitzman: So Homo Economicus takes the gift and just says, thank you.

Thomas Talhelm: Yep, thanks, sucker.

Hal Weitzman: And doesn't do anything, no reciprocity at all?

Thomas Talhelm: Right.

Hal Weitzman: And so what's the Homo Economicus model of work, just your work for the highest possible amount, for the least amount of work, for the most amount of compensation?

Thomas Talhelm: It's a strict contract. It says, you're paying me for what? Okay, I'm going to do that exact thing. And a homo psychologist idea of work is to say, "Well, there's relationships, there's hidden expectations. Even though you didn't say this thing, I know what you really wanted me to do this other thing. Or maybe I just want to do a really good job because I think this is worthwhile. So I'm not calculating the dollars and cents about the tasks that I'm doing. I have all these other concerns, human social relationships, identity, things like that."

Hal Weitzman: Okay. And I know you've written about WEIRD cultures before. Just remind us what WEIRD cultures are.

Thomas Talhelm: Yeah. So it's basically a stand-

Hal Weitzman: It's an acronym, obviously.

Thomas Talhelm: Yeah. So it's basically a stand-in for Western individualistic countries. The acronym is meant to be thought-provoking. It's meant to be... I don't know, get people to think. The idea is that people in Western cultures are often outliers in psychological research. You give a task to people around a hundred cultures around the world, Western cultures tend to be on one end of these different tasks, these different psychological measures.

It literally stands for Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic. So those are the characteristics of the cultures that tend to be that way. Although it's not meant so literally, it's really a stand in again for Western individualistic cultures.

Hal Weitzman: And is the idea that Homo Economicus is a product of that Western culture, that Western way of thinking?

Thomas Talhelm: I do think that people would make that argument, that the Homo Economicus model sounds like it describes Western individualistic cultures, especially in the sense of not caring about obligations as much, being independent from other people, and being self-focused.

Hal Weitzman: And it means this is also a sideswipe in a way at some behavioral science that is projected out from samples that have just taken a particular demographic group that happens to be in the UK, or the US, or whatever, and saying this is what human nature is about.

Thomas Talhelm: That's exactly what I was dumpster diving for. I mean, that's where my mind was going looking at Devin's data. He presents this mega study saying 10,000 people, and look at money just always outperforms these psychological interventions. I said, what if we looked at the data from India? Are we drawing this conclusion based mostly on American participants? And how representative is that of the world?

And so when I was looking through his data, that's the thing I was finding. We talked about a gift condition. There was also a charity condition where you, for every extra, I think it's a hundred button pushes you do, you can earn a penny for charity. And so there's one condition where that money goes to you, and there's another condition where that money goes to charity. The Homo Economicus prediction, super simple, if that money's going to me, great, I'm going to try hard. If that money's going to charity, all right, I don't care. And that economic model fit pretty well with what the Americans did. They worked pretty hard when it was the money going to them. When it was going to charity, they dropped off a lot.

Participants in India actually didn't drop off. They worked just as hard for the self as they did for charity. That's interesting. And so what it suggests is, okay, maybe this model that we have is a better description of some cultures than other cultures. That's the idea.

Hal Weitzman: Okay. So we've talked about financial motivations and the psychological motivations. And you've made the point that you can follow your psychological motivations and that can lead to long-term monetary gain, but it could leave you more vulnerable to being exploited. Just dig into that a little bit.

Thomas Talhelm: Yeah. So we ran a follow-up study. So one downside of dumpster diving is that it's discarded data. It's not designed to ask the questions that I wanted to ask. So for example, there weren't a lot of participants in India, something like 15% of the sample.

So we ran new studies and we decided that button pushing task was kind of silly. Let's do something that's a little bit more work like. And so we designed a new study. We gave people... You know those captcha images that you take to prove that you're a human on a website? We told participants that we were-

Hal Weitzman: How many traffic lights do you see in these pictures or whatever?

Thomas Talhelm: It's super simple like that. We had these pictures where it's just, tell us, is there a building in this picture? And sometimes it's a flower and the answer is no. Other times it's the Sears Tower and the answer is yes.

So we gave people a bunch of those. We told them we were developing a machine learning image classification algorithm, and that that's what they were helping us doing with this task. And what we told them is, we're going to pay you to do 10 of these images. So again, we're on this MTurk platform and some other platforms, we'll pay you to do 10 images. At 10 images, you're done. You can stop. You get your money, we're not going to pay you extra. That's it. But they can keep going if they think that's the right thing to do, or if they feel compelled or whatnot.

And so one of the interesting things to track in this study is do people work longer than they're contractually obliged to? And that's where I think the cultural difference can lead to some forms of exploitation. What we found is that our American participants, we also ran this in the UK, they tended to quit as soon as they could. You said 10 images. All right, I've done 10, I'm done. Participants in India, in China, in Mexico, in South Africa, they tended to work beyond 10 images even though they weren't being paid extra for it.

And then they had to pass comprehension checks. We made sure they understood the instructions.

Hal Weitzman: It wasn't that they had lost count or anything?

Thomas Talhelm: That's right. And we actually make it explicit. We say, you've completed 10 now. You can stop now or you can continue. So we try to make it super explicit. And we still get this cultural difference where some people are working harder even though they're not making extra money, even though they don't have to.

Hal Weitzman: What was the division between those other groups?

Thomas Talhelm: Oh, so are there differences between-

Hal Weitzman: Diversity, yeah, between India and South Africa, whatever.

Thomas Talhelm: Yeah. Okay. So South Africa tends to be a little bit more Western in terms of people's behavior. That could be because of its history of colonization. China and India tend to be a little bit less Western in people's behavior.

So for example, one of the things we did was calculate what we call the money advantage. So we run money conditions where we pay you for every image that you complete. And then we have these psychological conditions where we just give people social norms like, oh, people tended to do 160 images. And so you can calculate, okay, how much better is money than the psychology?

In places like the US and the UK, it was over a hundred percent better. So people's output doubles when you pay them as opposed to just telling them a social norm. In China that was closer to 20%. So money was still better than a social norm, but not that much better. So we're talking like a hundred percent versus 20%, right? That's the magnitude of the cultural difference.

Hal Weitzman: If you're enjoying this podcast, there's another University of Chicago podcast network show that you should check out. It's called Entitled, and it's about human rights. Co-hosted by lawyers and law professors, Claudia Flores and Tom Ginsburg, Entitled explores the stories around why rights matter and what's the matter with rights.

Thomas, in the first half we talked about your research on what drives people, what makes them work. And you talked about how there were these differences between WEIRD cultures, basically Western industrialized thinking, and how people behave in other parts of the world. And we talked a little bit about how psychological research doesn't necessarily take account of these distinctions.

And you were telling us a little bit about, before the break, about how you tested this and found indeed it was the case. You paid people to do a certain number of image matching or whatever, image identification tasks, and the WEIRD ones, the Western ones, once they've reached that goal, just immediately dropped off, whereas other people stayed on.

So how do you explain that result? Is it the people are obviously enjoying themselves?

Thomas Talhelm: Yeah.

Hal Weitzman: They're having a good time. Why are they carrying, persisting in doing this?

Thomas Talhelm: Yeah, so we think it's different ways of thinking about work. We think Western cultures are built around these explicit formal contracts and that people take them very literally. That's a big difference. I've lived in China, I've worked in China, I've had contracts in China. They exist, but I think people aren't taking them as literally. I think there's more of an expectation that you're going to read between the lines, or maybe the situation changes and that you're going to work with me to be flexible to adapt to that.

And so one of the things that might come out of that is to say, I know you said 10, but that was really quick. It didn't seem like I really put in an honest effort there. It seems like maybe you paid me more than I think I should have worked, so I'm going to do a little bit extra.

Or maybe you care about your reputation. One of the things that we found after running this study, people would send us their resumes after this. That only happened in non-Western cultures where we would run these studies. People would send us their resumes afterwards. And the idea there is, I think what they were trying to do is create a reputation or a strong impression that could lead to future benefits down the road.

So our Western participants were thinking, no, this is a one-off. It's contained right here. Everything you wrote in the contract, in the consent form, that's what we're doing. Our participants from non-Western cultures were thinking maybe there's something more going on here. Maybe there's a relationship, maybe there's a reputation. And those things would pay off over the long run. So yeah, maybe I'm working a little bit more right now, but that might have benefits down the run.

Hal Weitzman: Okay. And so how do you account for the... I mean, they presumably know this is an experiment that they're part of, and it's run by someone who's at the University of Chicago. I mean, we talked about some of the relationship. There's a power dynamic there that somebody from Chicago might just say, well, okay, they're running a study, they're paying for it, I'll do it as long as you pay me. Whereas somebody in India might think, well, there's an opportunity to connect with a professor at the University of Chicago. Who knows what might come with that?

So how do you account for that dynamic?

Thomas Talhelm: Yeah. So one fun way... So there's tons of questions like this about, oh, what differences are there between nations? The value of a dollar is also something that differs, that we try to take care of. One way to get around all this sort of question-

Hal Weitzman: Right. Because people are getting paid the same regardless of where they are?

Thomas Talhelm: That's right.

So we did run other studies where we used economic techniques to try to make the pay subjectively equivalent. So we ran another condition, for example, in the United States where we raised the pay in the US to try to make it psychologically equivalent to other cultures.

But again, there's a real cherry on top in this study I think that's really fun. We ran a condition in India where we randomize people to take the study either in English or in Hindi. This is based on the idea that people who speak different languages have different cultural scripts in their heads that are activated by the different languages. And so the idea is that English is a vehicle of Western culture. People in India may associate it with British culture, American culture, and Hindi is going to remind people of the local culture.

And so we randomly assigned people to take the same study either in English or in Hindi. And what we found is that money was more motivating to people, in other words, it led to more work when it was in English than when it was in Hindi. And so the idea is like, oh, the prestige of the study, who you're working for, all this stuff, all that's the same. The only thing that's differing is the language that we're asking you to use in this study. And that alone was enough to change the power of money, which is pretty cool.

Hal Weitzman: So if you're bilingual, you think about, what motivates you is different depending on what language you're thinking in?

Thomas Talhelm: Yeah, like the task, what are we doing right now? Is this a simple work task or is this a relationship? The language alone seems to be enough to prime that.

Hal Weitzman: I also want to talk to you about the gender differences you found in this study. And you found that the differences are biggest in the countries with the most legal gender equality and economic development, which sounds counterintuitive. So tell us about that.

Thomas Talhelm: Earlier we asked this question, the Homo Economicus model, how well does that apply to different cultures? But you can also think of things other than national culture. And gender is one.

I think in the United States people stereotype is that the Homo Economicus model is sort of a male thing. I think people associate economics with men. I think people associate selfishness and calculating work benefits as a male thing. And people associate the opposite of that, relational concerns, thinking about other people as something that describes women more than men.

And so with all this data, we said, well, we can just look at that. And what we found is that that intuition is true in our Western cultures. So in the US and in the UK, if you look at, for example, the classification task where people can stop at 10 images, you can just say, okay, what percentage of people stop as soon as they can? They get their pay and they're out, versus how many people continue? And the percentage stopping as soon as they can was higher for men than it was for women. And that fits with the idea that the Homo Economicus is male. So men were more likely to quit than women as soon as they could.

But then when we looked at this in India, China, South Africa, Mexico, it actually, it didn't just go away, it actually flipped. So it was the women that were the more calculating. It was the women that were quitting as soon as they could. And it was the men that tended to work longer. That's weird, right? I mean, if Homo Economicus is inherently male, why is this changing around cultures?

Hal Weitzman: Okay, so how do you explain it?

Thomas Talhelm: We don't have a great explanation. I mean, one idea that I've heard suggested is perhaps the demands on women's time is higher in non-Western cultures, so perhaps there are expectations both to work and to do more things around the homes like gender division of labor. If that's the case, then perhaps women just have to be more calculating about their time because there are more demands on their time. That's one possibility.

Another possibility is the idea that Homo Economicus is male, maybe that's somehow cultural or maybe that's somehow in the media. Perhaps exposure to economics training is somehow reaching men more than women in Western cultures. But that's not perhaps the case where fewer people are studying economics and going to university. It's one possibility. We don't know.

Hal Weitzman: Okay, fascinating. Now, I know that people from the different cultures that you studied in the study had strong feelings about it. What did they tell you? What did they say?

Thomas Talhelm: Yeah, so I posted a fun graph on Twitter. This was for a little follow-up study. We ran a version of a task again where you could quit right at a contractual minimum or you could go and complete the whole task. And we had something like 40 cultures around the world. And the percentage who worked beyond the contractual minimum and completed the whole task varied wildly across cultures. The UK was the lowest. Something like 10% of people completed the whole thing. In Turkey, Madagascar, Brazil, it was close to 70%. It's just a huge difference there.

And I posted this online. I was just trying to get people to go to my PhD student's talk at a conference. The next day he texted me and he said, "That tweet has been seen by a million people and there's so many people commenting on this." And kind of freaked out because you never know how your research is going to be received. And talking about cultural differences, maybe some people are going to be upset.

What I found when I finally logged onto Twitter and looked at people's reactions is that people on both sides were super happy to be on both sides. People in Brazil and Turkey were like, "Look how hardworking we are." One interesting thing was, "Look how smart we are. We understand that you said just do this thing, but you really wanted this thing. That's a smart, mature thing to do." Super interesting.

People in the UK on the other hand, we're super happy that they were the lowest around the world. And I think the idea that, I mean literally to be-

Hal Weitzman: In other words, we had to do the least to get the maximum benefit?

Thomas Talhelm: I think they were interpreting it as-

Hal Weitzman: We understood the task.

Thomas Talhelm: We understood the task, but also we're avoiding being exploited. This is like power to the worker. That's the screw the boss, we're defending our rights. I think that was it. Literally two people said, "I've never been more proud to be British than looking at that graph." And so to me it was super fascinating.

Hal Weitzman: I can tell you there's not that many reasons to be proud to be British, so maybe we're grasping at any straws we can.

No, but that's interesting because it just suggests that the whole... The thing you're talking about, you say some people say, "Well, you said this, but you actually meant this," that is cultural as well. In other words, if I'm dealing with someone in Turkey or Brazil, I should be aware of that, that perhaps there's more than what they actually say. And vice versa. If you're dealing with someone in the UK, you know that when they tell you to do this, they really mean just do that. Right? Does that make sense?

Thomas Talhelm: That's exactly it. I think cultures differ in how literal people expect communication to be. And if you're going to be working across cultures, I think that's something you need to understand.

Hal Weitzman: So this is not necessarily so much... This is as much about motive, what motivates us to work as about communication, how we talk to each other?

Thomas Talhelm: Yeah. That's exactly it. I think there's a huge communication component in this.

Hal Weitzman: Okay. Well, Thomas, thank you so much for coming on the Chicago Booth Review Podcast, talking to us about your research. And I'm glad that you survived the dumpster diving.

Thomas Talhelm: Yeah, and I came out with something, a nice find. Yeah.

Hal Weitzman: That's it for this episode of the Chicago Booth Review Podcast, part of the University of Chicago Podcast Network. For more research, analysis, and insights, visit our website at chicagobooth.edu/review. When you're there, sign up for our weekly newsletter so you never miss the latest in business-focused academic research.

This episode was produced by Josh Stunkel. If you enjoyed it, please subscribe, and please do leave us a five-star review. Until next time, I'm Hal Weitzman. Thanks for listening.

Listen to more of the Chicago Booth Review Podcast >>

Chicago Booth’s Eugene F. Fama explains his skepticism about the world’s biggest cryptocurrency.

Capitalisn’t: Why This Nobel Economist Thinks Bitcoin Is Going to Zero

A Q&A with Chicago Booth’s Canice Prendergast about the forces that influence prices for artwork

The Market for Contemporary Art Is a Little Bananas

In Chicago, a combination of policies could generate substantial improvements for the average traveler.

The Secret to Better Public Transit? Make Drivers Pay for It

What’s the best way to set and manage goals and exercise self-control? In this Tiny Course, a series of short videos and quick quizzes can help you start to master the science of motivation.

Get It Done with Ayelet FishbachRegulation could help lead crypto from the Wild West to Wall Street.

In Stablecoins We Trust?

Research examines the role of intangible assets such as patents and trademarks.

Why Thousands of M&A Deals Are Avoiding Antitrust Scrutiny

A Q&A with Chicago Booth’s Steve Kaplan about decision-making in venture capital.

For Startups, the First $1 Million Is the Easy Part

Investors are best to find a market anomaly before researchers do.

Market-Beating Stock Strategies Don’t Last

With the right approach, mistakes can be the fuel for your greatest victories.

The Incredible Power of Being Wrong

Rather than being more financially cautious after a layoff, many become less so.

Job Loss Can Lead to Risky Decision-Making

The discipline that makes companies run better can help you too.

Life Lessons from Operations Management

The EU’s failure to reform after emergencies has left the euro vulnerable.

Europe’s Next Financial Crisis Could Be the Big One

Economists evaluate the likely impact of programs to bring researchers to the EU.

Can Scientific Recruitment Accelerate European Innovation?Your Privacy

We want to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why we collect particular information when you visit our website.