In 2018, the Executive MBA Program celebrates its 75th anniversary and looks to shape new generations of leaders.

- By

- January 10, 2018

- Community

The year 1943 dawned upon a world at war. Little more than a year had passed since the United States entered World War II, but American life had already been rocked to its core. All personal car production had ceased, as Detroit’s Big Three factories churned out tanks, equipment, and billions of rounds of ammunition. By the end of the year, two million men would leave the workforce to serve in the military. And American women—many working outside the home for the first time—marched into factories in unprecedented numbers to replace them. It was an era of change, as Americans struggled to meet the challenges of the day.

Chicago Booth entered that changing landscape when it launched the world’s first Executive MBA Program in 1943. The school recognized the need for experienced leaders to apply their knowledge and training to urgent tasks and expand the capacity of American industry. For the first time, there existed a course of rigorous business education tailored to the specific needs of mid-career managers.

Or, as an early Executive MBA brochure put it, “The task of war is primarily one of co-ordination of men and materials in the work of industrial production; it is a problem of management.”

In the 75 years since its inception, the Chicago Booth Executive MBA Program has continued to adapt to meet the evolving needs of the business landscape. It has implemented concepts of human capital pioneered by a Nobel Prize winner and taught generations of senior leaders around the globe how to maximize their own professional and personal growth, while also developing the people they manage. Over the decades, the program has encouraged executives to experiment with different leadership styles and to develop what Booth professor Linda E. Ginzel calls their “leadership capital” throughout their careers. Born in the midst of global disruption and change, the Executive MBA Program has trained successful leaders to rise to the challenges of a rapidly evolving world. From 1943 to today, the Executive MBA Program has given students a world-class skill set to thrive in the business world in the days, years, and decades after receiving their Booth diploma. “The Executive MBA Program gives students a more critical, more structured way of thinking about business problems, and that helps them make better decisions and be better leaders,” said Richard Johnson, ’14 (EXP-19), associate dean for the Executive MBA Program, Asia and Europe. “They also gain a level of confidence they never would have had around what they’re capable of achieving. The experience is transformative.”

The success of Booth’s Executive MBA Program inspired hundreds of institutions around the world to develop their own programs for mid-career students. Chicago Booth’s program has expanded around the world, too; in the 1990s, it became the first US program of its kind to establish a campus outside the country. Today, Booth remains the only business school with permanent campuses on three continents, and draws students and faculty from around the globe. Executive MBA alumni have made an indelible mark on the world—and on Booth—over the decades. George Conrades, ’71 (XP-28), led Akamai Technologies back from the dot-com bust to being a billion-dollar company. Sister Sheila Lyne, ’80 (XP-44), served as commissioner of public health in Chicago. José Antonio Álvarez, ’96 (EXP-1), navigated Spain’s Banco Santander through the European banking crisis. Tandean Rustandy, ’07 (AXP-6), founded one of Indonesia’s most successful businesses, and his $20 million gift to Booth in 2017 set the foundation for the future of social impact at the school. The list of Executive MBA Program alumni who have reached the C-suites of Fortune 500 companies, founded well-known businesses, and advanced the public interest on crucial issues goes on and on.

The origin of the success of all its alumni, however, lies in the Executive MBA Program’s founding mission. When the United States entered World War II in 1941, the country faced enormous logistical challenges. Convoys of merchant ships had to maneuver past German U-boats in the Atlantic; huge numbers of troops had to travel thousands of miles across the Pacific. The war was won, argues historian Paul Kennedy, through operational excellence. “Small groups of individuals and institutions, both civilian and military, succeeded in enabling their political masters to achieve victory,” Kennedy wrote in Engineers of Victory: The Problem Solvers Who Turned the Tide in the Second World War.

In 1942, Willard Graham, an accounting professor at the University of Chicago, began making plans to develop more of those problem solvers. He proposed a new type of MBA program—one that was designed for experienced managers to help strengthen the leadership of American business.

The first Executive MBA class entered the university in 1943: a cohort of 52 students, representing some of the largest corporations in Chicago. Among that first class were a manager from the budget and financial studies division of Marshall Field’s, a supervising engineer at Commonwealth Edison, and an assistant district traffic superintendent for Illinois Bell Telephone.

After the war ended in 1945, the focus of the program shifted, but demand for education of all types was booming. “Many returning veterans were very anxious to get back to work and develop the skills that they needed to make contributions,” said Harry L. Davis, Roger L. and Rachel M. Goetz Distinguished Service Professor of Creative Management, and former deputy dean for MBA programs. “There was a lot of talent coming into the university, not just in the Full-Time Program, but also people who were more senior.”

The first Executive MBA students completed the program in 1945. In the early years, students were typically in their 40s or early 50s, with decades of work experience but little formal business education. They were taught by the same faculty as students in the Full-Time MBA Program—unusual for part-time programs of that era.

“The very idea of educating people who had significant work experience was a revolutionary way of thinking.”

— Glenn Sykes

Graduate business education was still a young field at this point, said Glenn Sykes, associate dean for Evening MBA and Weekend MBA Programs and program innovation. Before Booth launched the Executive MBA Program, “most MBA students came through right from an undergraduate program,” said Sykes, who previously served as associate dean for the Executive MBA Program in Europe and Asia. “The very idea of educating people who had significant work experience was a revolutionary way of thinking.”

By the 1950s, Executive MBA students at the university were studying economics, accounting, and statistics for managers; developing a general management approach to business problems; and examining the responsibility of business leaders within social, economic, and political systems. Tuition in 1956 was $100 a course, or $1,200 for two years; the average indexed yearly income at the time was about $3,500.

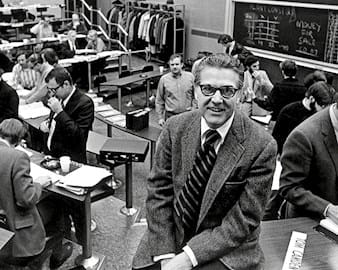

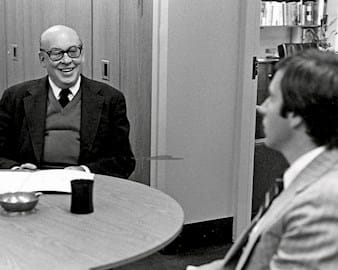

Despite the program’s success, other schools didn’t jump on board until 1964, when Michigan State University launched its own Executive MBA program. Today, there are 300 such programs in at least 30 different countries. That growth is due partly to the work of UChicago professor Walter David “Bud” Fackler, director of the Executive MBA Program from 1970 to 1987, who cofounded the EMBA Council in 1981 to help programs worldwide share knowledge and best practices. In 1987, the EMBA Council established the Bud Fackler Service Award—honoring Fackler as its first recipient—to recognize contributions to the EMBA Council and to EMBA programs worldwide.

“Bud was very, very loved by all of his students and by other faculty, and he had this amazing presence,” said Patty Keegan, associate dean for Booth’s Executive MBA Program North America and the 2010 recipient of the Bud Fackler Service Award. Upon Fackler’s death in 1993, alumni began fund-raising in his name, resulting in what was then the largest such pooled gift fund in school history. The funds created the Walter David “Bud” Fackler Professorship, currently held by John Huizinga.

In addition to creating the first Executive MBA program, Chicago Booth designed the first US Executive MBA program to expand abroad without an international partner. When Booth began teaching MBA classes in Barcelona in the 1990s, only faculty from the school were used. This continues to this day at the campuses in London and Hong Kong.

One might imagine that the decision to establish a campus in Barcelona, which opened in 1994, was based on a rigorous, Chicago Approach–style analysis of the market potential in various European cities. But according to Davis, that’s not quite how it happened. In the early 1990s, when he was working in the Deans’ Office, Davis welcomed three visitors who proposed that Booth start a full-time MBA program in tiny Andorra. “I must say, I was polite,” Davis recalled. “But after they left, I thought, ‘This is really quite an absurd idea.’”

Yet the conversation sparked a series of discussions about launching an Executive MBA program in Europe, in the slightly bigger metropolis of Barcelona. “One thing led to another,” Davis said, “and about three years later, we had an Executive MBA Program in Europe.” Classes at the Barcelona campus began in 1994, and Booth took a truly unique approach for a program of its caliber. Instead of partnering with local faculty, as other schools often did, Booth sent its own renowned faculty from Chicago to teach at the Barcelona campus.

Robert Wardrop, ’96 (EXP-1), graduated in the first class of European Executive MBA students. “That two-year experience ignited an interest in learning that was latent, that I didn’t know I had,” said Wardrop, who pivoted his career from finance to academia, and now is the director of the Centre for Alternative Finance at the University of Cambridge. “I came out of that with a capacity to explore intellectual curiosities, which is very much a Chicago ethos.”

Just as the pace of economic change has seemed to accelerate in the new millennium, so has the rate of change for the footprint of the Executive MBA Program. In 2000, Booth launched the Executive MBA Program in a third location, Singapore, becoming the first US-based graduate business school with a campus in Asia. In 2005, the Barcelona campus relocated to London, where it resides in the heart of the city’s financial district, amid some of the world’s most powerful brokerages, insurance companies, law firms, and banks. In 2014, the Asia Executive MBA Program relocated to Hong Kong. In November 2018, the Hong Kong program will move to the new Francis and Rose Yuen Center, supported by a $30 million grant from the Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust, Hong Kong’s largest community benefactor. “One part of our mission is to have a global impact by influencing leaders worldwide,” Richard Johnson said. “The Yuen Center will allow us to amplify our ability in Asia to make an impact, to educate, and to provide thought leadership.”

Student demographics in the Executive MBA Program continue to change as well. Its students today are younger, with a wider range of backgrounds. The average age of the incoming class of 2017 was 37, and students had an average of 13 years of work experience; the cohort represented 46 nationalities. The high caliber of students has remained constant, however. “The strengths of students in our Executive MBA Program over time have had the same core elements: wanting to be successful, having a strong work ethic, and being very committed to their professional development,” Keegan said. “I don’t see that changing anytime soon.”

Today, it seems obvious that a person’s skills and knowledge are another form of economic capital. But that was a radical concept 60 years ago when University of Chicago economists pioneered research that revealed the links among education, individual welfare, and a thriving national economy. Over its 75 years, the Executive MBA Program has pushed accomplished senior leaders to further develop their skills and learn how they can inspire those they lead to do the same.

Just a few years after the program’s founding in 1943, the GI Bill provided funds for millions of US military veterans to continue their educations. The bill also inspired a young University of Chicago economist named Gary Becker, PhD ’55 (Economics), to study the connection between education and income.

Becker developed his initial ideas into a series of papers and a pathbreaking book, Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education. Published in 1964, the book outlines an economic theory that explains how investments that make people more productive, such as education, pay off in the long run. Becker portrayed humans as essentially rational beings, and he applied his economic analysis to behaviors such as marriage and crime. When Becker was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1992, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences noted, “It is hardly an overstatement to say that the human-capital approach is one of the most empirically applied theories in economics today.”

Executive MBA students benefit from the insights of Booth professors—such as Kevin M. Murphy, PhD ’86 (Economics), George J. Stigler Distinguished Service Professor of Economics, and Robert H. Topel, Isidore Brown and Gladys J. Brown Distinguished Service Professor—who continue to build on Becker’s work. Murphy and Topel have studied how market dynamics, such as increasing technology and physical capital, favor skilled workers in the global economy. At UChicago’s Becker Friedman Institute—which fosters research exemplified by Becker and fellow economic luminary Milton Friedman, AM ’33—Murphy and Topel lead the Health and Human Capital Project. It explores how human capital heightens the incentives and abilities of people to invest in their own health, while health amplifies the incentives to invest in other forms of human capital.

Investing in human capital goes beyond developing the most apparently marketable skills. “In human capital terms, some of the most precious skills to have in the market right now are technical skills,” Wardrop said. “While in the short term, it’s rational to invest in a skill set directly applicable to artificial intelligence, for example—that will drive my highest return—it’s not just about the return to the individual. It’s about the return to society.”

More than 25 years after Becker’s Nobel recognition, Executive MBA students are still finding relevance in his theories and the massive body of knowledge around human capital that his work spawned. As managers, they develop a stronger understanding of human capital to attract and retain top talent in their businesses.

“The day-to-day life of business people is an incredible laboratory for growing self-awareness and self-discovery.”

— Harry Davis

Through the Executive MBA Program, students learn to redefine their roles—and to expand the possibilities for their careers. “I have students who say to me, ‘Well, I’m just a manager,’” said Linda E. Ginzel, clinical professor of managerial psychology. “‘Someday, when I’m a leader, then I’ll be able to do all these other great things.’”

Ginzel offers a dramatic departure from this mind-set. Instead of labeling themselves as either managers or leaders, she tells her students that they are executives who both manage and lead. Deciding whether to lead or manage is a behavioral choice based on your values and goals as well as the particular situation you confront. Learning to choose the best actions for the circumstances is a process that Ginzel describes as developing “leadership capital,” or “the wisdom to decide when to manage and when to lead, together with the courage and capacity to act on your choices.”

“I term my approach ‘leadership capital’ as an homage to human capital,” Ginzel said. “It references the University of Chicago’s intellectual contribution that intangible assets can be invested in and managed similarly to more familiar types of capital, such as physical or financial assets.” Ginzel’s approach helps students adapt to a rapidly shifting global marketplace and develop their own strengths and perspectives. “In my classroom, we speak often about the frameworks that allow us to think more complexly about business issues across industries, economies, and geographies,” she said in an address at the Executive MBA graduation ceremony in March 2017. “I emphasize building our own personal frameworks. When we create our own structures and reduce our reliance on externally provided ones, we increase our ability to handle ambiguity.”

Current Executive MBA student Adja Diakite has already begun to apply leadership lessons from Booth in her work on interest rates and FX derivatives at Deutsche Bank in London. “You are with some of the smartest and brightest students from around the world, coming from different cultures,” said Diakite, originally from Mali, West Africa, who studies at the London campus. “You learn with them to build your leadership journey. It has enabled me to be a better listener, to prepare more for initiatives I want to take forward, to ask myself the right questions, and to build up my communication and presentation skills.”

Diakite credits leadership lessons at Booth with inspiring her to help organize the inaugural Chicago Booth Africa Forum, which took place in London in April 2017 and focused on the theme, “Changing the Game in Africa.” The forum brought together alumni and business leaders in media, private equity, banking, development, and small business to discuss how Booth can share insights into the emerging market, strengthen the Booth brand on the continent, and recruit more talented students from Africa. “It was a great leadership challenge: putting together alumni across Africa and leaders, politicians, and corporations to make sure Booth is part of the conversation,” Diakite said.

Booth’s Executive MBA Program provides students with the tools and frameworks to draw leadership lessons from their experiences, long after they have left the classroom. “Leaders need to continue to learn from their experience,” Davis said. “That requires experimenting, collecting data, reflecting on the data, talking to others. The day-to-day life of business people is an incredible laboratory for growing self-awareness and self-discovery.”

“Our program was founded during a time of tumultuous change in the world, and in this day and age, change just keeps coming even faster.”

— Patty Keegan

“Could we imagine five years ago that we would be living in the world we are in right now?” asked Maria Scott, ’17 (EXP-22), cofounder and CEO of TAINA Technology Limited. “There’s change at a phenomenal pace.” TAINA won the 2017 Global New Venture Challenge by helping global financial institutions automate their regulatory compliance, thus saving cost, mitigating risk, and improving their customers’ experience.

By grounding students in the Chicago Approach—a set of fundamental, discipline-based tools to solve business problems—the Executive MBA Program allows alumni like Scott to innovate and adapt to tomorrow’s business environment, no matter what changes lie ahead. While the world today looks very different than it did in 1943, one constant remains: the need for leaders who have the skills, educational framework, and confidence to adapt to change.

“Our program was founded during a time of tumultuous change in the world, and in this day and age, change just keeps coming even faster,” Keegan said. “One of the challenges is responding to that and still being able to provide a consistent, rigorous business education to students throughout the world.”

As more students enter the Executive MBA Program with business ideas they want to develop, Booth has expanded avenues for entrepreneurs to hone their plans, get feedback, and win funding. The Global New Venture Challenge class, taught by Waverly Deutsch, clinical professor and academic director of university-wide entrepreneurship content, is an intensive six-day course in which teams of students develop business and financial models and present to panels of investors.

“What’s so exciting about our students in the Executive MBA Program is that they have extensive business experience from all over the world,” Deutsch said. “It’s particularly relevant when you’re dealing with issues of entrepreneurship, because it is subtly different based on the country you come from. The fact that we have country experts in the room with us can make it a much more interesting conversation.”

The Executive MBA Program teaches students not only how to manage change in their own careers, but also how to introduce a product that brings change to customers—in Scott’s case, within the financial market. “You can never impose change,” Scott said. “You can only grow into it together as a collaborative process, and this is only possible if you deeply understand the customer’s pain points. Booth has been amazing: teaching the biases, teaching us the science and the psychology of the decision-making process, making us conscious of our own biases, helping understand why change is never easy at the deepest human level, and what we can do to help overcome these challenges.”

The decision to pursue an Executive MBA involves a very business-minded question: What is the return on investment? With life- and career-spans increasing, the two-year investment in the Chicago Booth Executive MBA offers a quantifiable ROI that accrues over decades: higher salary, accelerated career progress, increased impact at work, and personal satisfaction.

But perhaps the biggest return on investment in the Executive MBA Program is something less quantifiable. “I had my rational reasons for why I wanted to do the Executive MBA—my need to understand more about finance, my income potential,” Wardrop said. ”However, what I didn’t expect—and what was the biggest outcome of the program—was confidence. How do you price a change in confidence? That’s very difficult to do.

“Do I feel that has produced enormous dividends to me over the course of 25 years? Absolutely. And it wasn’t in my ROI.”

We'd love to hear your Booth memories, stories, connections...everything.