Imagining A More Accessible Society

Four innovators are dedicating their time to forging a more inclusive world for disabled and chronically ill people.

Imagining A More Accessible Society

James Fish Jr.

President and CEO

Waste Management

“Great companies today are focused not just on their financials but also on the question, what purpose beyond shareholders are we serving?”

After James Fish Jr., ’98, had worked at Houston-based environmental services company Waste Management for four years in pricing and finance roles, he wasn’t sure whether he wanted to continue with the company. His father-in-law, a pipe fitter, gave him some advice that changed his life. “He said, ‘If you really want to understand the business, ask to move into field operations,’” Fish recalled.

He took the advice and was transferred to Boston, where he attended early-morning meetings with truck drivers and recycling workers, gaining insight about the details of their jobs. “It helped me learn that there are 50,000 people here, and I am not the most important one,” he said.

Fish remembered the importance of that lesson when COVID-19 hit the United States in March 2020. He quickly reassured hourly workers that they would continue to be paid no matter how long the pandemic lasted. Then he leveraged Booth’s alumni network to help his office employees transition to working from home. He reached out to Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella, ’97, who helped him get thousands of Microsoft Surface tablets shipped to Waste Management’s headquarters in Houston in just a few days.

Fish strives to make Waste Management a “people-first” company. The same spirit inspired him to choose Chicago Booth for his MBA. “I am a big fan of Milton Friedman and his book Free to Choose (1980), and I think of myself as a compassionate capitalist,” he said. “To me, the University of Chicago best defines that.”

Madhav Rajan:

Hi, I'm thrilled to introduce James Fish Jr., Chicago Booth's 2021 Distinguished Alumni Award winner in the Corporate category. Jim is an alum of the Booth class of 1998. He is president and chief executive officer of Waste Management, which is that the gigantic Houston based provider of comprehensive waste management services. And he also serves on the company's board of directors. Jim has been with Waste Management since 2001, and he's had several key positions in the company, including senior vice president for the Eastern group, area vice president for Pennsylvania and West Virginia, market area general manager for Massachusetts and Rhode Island. He's also been vice president of price management, director of financial planning and analysis. He became CFO in 2012, and president in July of 2016.

Prior to Waste Management, Jim held finance and revenue management positions at Yellow Corporation subsidiary, WestEx, at Trans World Airlines, and America West Airlines. He began his professional career at KPMG Peat Marwick. Jim earned a BS in accounting from Arizona State University, and then his MBA in finance from Chicago Booth. Jim is also a certified public accountant. Congratulations, Jim, and thank you for speaking to us today.

James Fish Jr.:

Thanks Madhav. How are you?

Madhav Rajan:

I'm doing well, thank you. Again, it's a pleasure to be able to speak to you. So I thought I'd begin with a question that all of us see. So at Harper, there's a big sign that says, "Why are you here and not somewhere else?" So perhaps you could just sort of speak to that more broadly, and then I could delve into specific questions as we go along the way.

James Fish Jr.:

It's really interesting because I have seen that sign. And when I first started thinking about a graduate program, really there were three programs that I thought about. One was, of course, Chicago, one was Wharton, and one was Stanford. My mom went to Stanford, so she was maybe a little bit biased towards Stanford. But what I really felt like in making the selection that Chicago fit me maybe the best. I was a big fan of Milton Friedman and loved his book Free To Choose. And really, I felt like what kind of defined to me was a compassionate capitalist maybe. And to me, Chicago best defined that. And certainly as I read Free To Choose and some of the other Friedman books, I felt like that's what he was really. So as I looked at, at where I wanted to really further my education, Chicago made all the sense in the world, with some deference to my mom. She, I think, was maybe a little disappointed initially, but she was thrilled at the end.

Madhav Rajan:

So maybe you could speak a little bit about Booth sort of helped you discover your why. So just broadly, what matters to you? How do you want to make an impact in the world?

James Fish Jr.:

As I think about, and this probably relates as much to Waste Management as it does to Chicago Booth, we want to have a purpose here. And I think Booth is teaching students the same thing. I mean, live with a purpose. It’s not just about—at WM, it's not just about the financials each quarter or each year. There's a purpose beyond it. And I think great companies today are focused on not just their financials, not just their shareholders, but also what purpose beyond shareholders are you serving? And I feel like that was a message that started to really be ingrained in me, well, I guess first and foremost, with my parents. Because we're all impacted by our parents.

But also in particular at Chicago Booth. I mean, the professors that I had and the classes that I had, that really came through to me. And so I carried that through in my career, not only at some of the companies I was with previously, but then into WM. And that's really certainly shown up as we've gone through a tough year in 2020. And so I can talk a bit about that. But that really is what I've tried to focus on is doing things with a purpose, not just focusing on what the quarter looks like, but what are we going to do purposefully?

Madhav Rajan:

Well, we'll get to 2020 and the difficulties that you've gone through. But before that, Jim, could you speak a bit about sort of what are some pivotal points in your career at Waste Management? Or before? What were some difficult decisions that had to be made or difficult challenges that you had to overcome?

James Fish Jr.:

I'm not sure it was a difficult decision so much, but every job I'd ever had was a white collar type job. I mean, whether it was an accountant position, or a finance position, or an office-type role. And my father-in-law was a pipe fitter from St. Louis, Missouri. And so in about 2005, I'd been with the company four years. I wasn't sure whether I was going to stay with a company or not. I'd been in a pricing role, in a finance role, but I really wanted to understand the business.

And so I talked to my father-in-law at the time. And he said, "Look, if you really want to understand the business, you should ask to move into one of the field operations. And even though you've never been in a field role, you should see if you can get yourself into one of those operations. That's where you really learn the business." And so it was a bit scary for me because I'd never managed truck drivers or recycle workers. I, I'd never been in a blue collar type managerial role. But the company agreed to move me, and they moved me to Boston, and then subsequently to Pittsburgh and Philadelphia.

But that first move to Boston, there was some trepidation there. As we moved out there, and my wife Tracy was very supportive in the move, but I think without my father-in-law...Sorry, I got a fly flying around me here. But if it had not been for my father-in-law encouraging me to make that move, I'm not sure I'd be sitting here today talking to you. That was a big move for me to move out. And one of the things that he said was, "Don't just sit in your office. Make sure that you go out to the field. And by the way, go out to a meeting. And if they have a safety meeting or whatever," which we did, he said, "don't go to the 6 a.m. meeting. If they have a 3 a.m. meeting, go to the 3 a.m. meeting. And by the way, if you only go once, then don't go at all. Because then they'll say, 'Well, yeah, he came out once, but we never saw him again.'"

So for every week over a period of seven years, I listened to my father-in-law. And he passed away a while, while we were living out in Pittsburgh. But every week I would make sure I went to a meeting. And part of that is carried through to what WM is today, which is really a people-first company. It helped me learn that there's 50,000 people here, and I am not the most important person. I may be the most visible person, but I'm certainly not the most important person.

Madhav Rajan:

You mentioned 2020. Perhaps you could speak a bit about the pandemic and the challenges that brought to WM. And what are some of the ways that you've been trying to take the company through that?

James Fish Jr.:

Well, 2020 has been really the most difficult year, I think for most of us. While we always have these constituents that we serve, whether it's customers, or whether it's employees or communities, or the environment, shareholders, we were distracted a bit from those normal constituents that we focus on each and every day. And we're focused on—necessarily focused on—the pandemic and focused on social justice, and some of those things that really reared up last year in 2020 and did serve as somewhat of a distraction. But not in a bad way. I mean, I think we needed to focus on those things. I think we needed to focus on social justice. And obviously we needed to focus on the pandemic because of the seriousness of it.

But we pretty quickly decided, look, first of all, the people-first approach that we've taken, this is the time to really shine on people-first. It's easy to be people-first in 2019 when we had a record year financially, and everyone's doing well, and so we call ourselves people-first, and everybody says, well, of course your people first, and it’s not that hard to be people first in a great year. 2020, when in March, everybody's jumping on the layoff train and immediately cutting back.

And I do remember, and I'll never forget, sitting in front of the television on the night of Saturday, March 21 and watching TV. And that was the only time in 2020, where I really felt maybe a little scared, honestly, a little worried. And I said, wow, I mean, if I'm feeling this way, then how is a truck driver who works for us feeling, how is a recycle worker feeling? Knowing that WM services, I think half of Major League Baseball teams. And that business is going to go away overnight. And we pick up a lot of universities, and all the way down to kindergarten. So big part of our commercial business is schools, and that's going to go away because there isn't going to be anybody at school. And all of the hospitality business that we service will go away overnight.

And those drivers knew that. And they're thinking to themselves, I'm watching this TV show that looks like the world's spiraling into the abyss. I might lose my job next week. And so I said, look, now's the time to really demonstrate that we are in fact people first. So we came out literally on Monday morning after that Saturday night scare on television. And said all of our hourly employees, which make up about, about 32 to 35,000 of our 50,000. All of our hourly employees, you don't have to worry about your hourly pay. You are guaranteed 40 hours. You will not lose your job as a result of this pandemic, because you had nothing to do with it. And if the pandemic last five years, and boy, I hope it doesn't, but if it lasts five years, you're guaranteed 40 hours.

And it really took that distraction away. And I think it helped us with the service of our customers and our communities. And by the way, it may even have helped us on the safety front. You're not driving down the road a 50,000 pound vehicle thinking, am I going to lose my job tomorrow? Because I can't afford to lose my job. I have bills to pay. I have a mortgage to account for. And we took that distraction away. And I think it was helpful, but it also, I think, proved to a lot of people that when we say people first, we truly meant what we said.

Madhav Rajan:

And so many of the people who work for WM were viewed as essential workers, right? And so that sort of kept going. How did you approach the whole work from home for the other parts of your organization? And what do you think the future of that is for WM?

James Fish Jr.:

We, along with just about everybody else, had to transition to home. So we have approaching 20,000, maybe a little less, of office workers in addition to those essential workers who are out on the front lines. So the office workers, we said, look, we've got to transition to home. I was able to, and this will come up in one of your later questions about, as I talk about the alumni network, but I was able to reach out to Satya. And I've known him through the alumni network and through the university. And say, "Look, we need laptops. What's the quickest you can get us some of the Microsoft Surfaces?" Because we'd called other companies. I won't name other companies that we called, but we called other companies. And they said, "It's six to eight weeks before we can...You're not the only person calling looking for laptops. Everybody's moving home. Everybody needs computers at home. Not everybody can pack up their desktop and take it home with them. So it's six to eight weeks."

And so I sent a note to Satya, and he immediately responded, I mean, within an hour, and said, "Let me get on this." And within probably three hours, I probably had 20 people texting me from Microsoft saying, "Okay, we can get you this." And within three to five days we had, I think it was 4,000 or 5,000 Microsoft Surfaces delivered. They were actually on a pallet sitting in the front of our office building. So whoever delivered—whoever the delivery company was, they probably should've taken them inside because you probably had $10 million worth of inventory sitting out in the front of our office.

But that really helped us tremendously transition. And we transitioned all 20,000 people home in 10 days’ time. I asked our chief digital officer, "How long would this have taken if I'd asked you this four months ago?" And he said, "I would have told you it's going to take 18 months." And we did it in 10 days’ time. So a credit to our whole digital team and our customer experience team, and all the teams that work worked on this. But honestly credit to Microsoft for getting us the equipment. We could have transitioned home, but we would have been sitting in front of a television set instead of a laptop.

Madhav Rajan:

And now is WM back fully now, Jim, in terms of the work from home? And sort of where do you see the future of that?

James Fish Jr.:

We're not back fully. We did transition back to the office on the 5th of October, and then we reversed course again. This has been a lot of ebb and flow with everybody with all businesses. And so we transitioned back to work from home about two months later, so towards the end of November. We haven't made a final decision on when we'll transition back fully to work from the office. I suspect it'll be sometime in probably early Q2. But we haven't made a full decision on that. So right now we're back to work from home.

You may be able to tell that I'm sitting here at our office. So we moved into a brand new office in Downtown Houston. Love to have you down and visit because it is fabulous. It's the most sustainable building in the state of Texas. And what's behind me is a 10-story live green wall. So it's pretty spectacular. So a lot of people are wanting to come in here. And we just started voluntary return this week. I expect we'll have quite a few volunteers at this building. But we have people working from home all around North America. And I expect, we'll probably transition back sometime in second quarter.

Madhav Rajan:

You mentioned the building, and of course the sustainability forum that you and Satya and Doug McMillon did, what does sustainability mean to you personally? What does it mean to WM? Is it a fad, or is this something that we should all be looking at going forward?

James Fish Jr.:

Well, it's certainly not a fad. Because we're the biggest recycler in North America, so it is our business. And the fact that that's we focus on, even at this golf tournament that we're hosting this week, for eight years in a row now we've done zero waste. Last year we had almost a million people at the golf tournament. So you can only imagine what that looks like. It's something that players have never seen before. They only see it our event on Saturday. We're not supposed to report how many attendees there were because Department of Homeland Security said, "It's so many attendees that we really don't want you to report the actual number."

But suffice it to say, the previous record was set in 2018, which for one day was 218,000. And it was quite a bit more than that. But we made a zero waste, and that's what it's been now for eight consecutive years where we recycle everything, or we compost it, or we donate it or turn it into energy, or what have you. And so sustainability is one of those purposes that I mentioned early in our conversation. And it's such a natural for us because it's a differentiator. We are at the biggest recycler in North America. And so recycling is what we do every day. It's not something that is a fad.

But it also serves to differentiate us. As other companies, whether it's Walmart, or Microsoft, or PepsiCo with Indra and her team when she and I sat down several years ago. Before she retired, we talked a lot about sustainability for PepsiCo, and how important that is for them. And as we think about providing that as a service provider to those companies, it becomes a differentiator. The better we are at it, the more likely PepsiCo or Walmart or Microsoft or other companies are to say, look, we want to be a customer of yours because you take this seriously. So it's a purpose that goes beyond just our care for the environment and our care for the earth that we all inhabit. But it also is something that differentiates us and becomes better for our shareholders.

Madhav Rajan:

So you talked a bit about the alumni network. I'd love to know on you connected to your alumni network? That was a great story about Microsoft helping you, and Satya. Are there other cases or instances of just how connected you've been, has it been helpful to you in your career journey?

James Fish Jr.:

It's interesting. Look, I don't have exposure to what Stanford or Harvard's network looks like or other great schools. Other than my mom always used to tell me that, wow, she was so impressed when we lived in Pittsburgh, that there was a University of Chicago network in Pittsburgh that was very active. And there's one in Houston that's very active. And she said, "I never got that from Stanford. It's amazing that Chicago has that." And really it's helped me to...I still stay in touch, not only with my classmates, but also with a number of folks within the University of Chicago alumni network. And so if I have a question, whether it's a question for an alum who's with an investment bank, whether it's with Goldman Sachs, or I mentioned Satya, of course, but it really helps to be able to reach out to someone.

And one thing I've noticed about the network at Chicago is that whether it's a student reaching out to me, whether it is whether it's an alum, maybe it's a professor, maybe it's you as dean. I mean, there's always this closeness, this willingness to respond and I've always felt, I'd say an obligation is maybe the wrong word but, but a sense of loyalty. So when a student reaches out and I'm guessing that that it's the same for others like Satya, but when a University of Chicago student reaches out and says, "Hey, I'd love to have some counsel on a topic or some advice," I always feel like, look, Chicago did so much for me and Booth was so valuable to me.

And really, if I were to pinpoint one reason why I'm sitting here beyond just my parents, it would be the University of Chicago and the Booth Graduate School. And so I feel like, gosh, I can certainly do something for today's students or for a professor. And so I think the network really is such a closely knit network. And I believe there's uniqueness in that compared to some of the other great schools out there.

Madhav Rajan:

Well, thank you. And I should note that you and Tracy have been incredibly philanthropic to the school and giving back to the community in so many ways. So we are really grateful for that. So I wanted to ask what does winning the Distinguished Alumni Award mean to you?

James Fish Jr.:

Well, obviously it's incredibly flattering to me. I'll tell you a story, Madhav. When I was first coming in for orientation, and I'd applied to these three schools, all great schools, and I'd picked Chicago. And I'm coming in for orientation and I'm looking around, and I'm thinking, gosh, I'm not even sure I'm really worthy of being in the room here. Because it was a room, literally, I felt like I was sitting in a room of geniuses, and I am not a genius. And so I'm thinking, first of all, I was flattered to even get in to the university. But secondly, I was amazed at the quality of my fellow students.

And so for a nanosecond, I was thinking, I mean, am I even going to fit in here because these are all brilliant people? And then a quote came to mind, and it's a very famous quote from Thomas Edison, that genius is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration. And I thought, okay, I can compete on the 99%, at least. I don't know whether I can compete on the 1%, but I can certainly compete on the 99%. And I think that's maybe in large part why I've been able to be successful in my career, is that while I'm not maybe in the same category as some of my fellow students who were MIT engineers, and Chicago undergrads, or Harvard undergrads, but certainly on that 99%, I felt like I can compete with an MIT engineer who happens to be a classmate of mine now at Booth on the perspiration side. And I think that might be a bit of advice for people who watch this is that really you may be part of that 1%, but really it's the 99%, I think, that that ultimately is going to separate you from others.

Madhav Rajan:

So our students, Jim, are always interested in sort of people's leadership journeys. And you had the great story about how in 2005 you decided to take a very different sort of role in order to learn more. Along the way, were there people who were mentors to you in Waste Management or other companies that sort of were people who sort of guided you as you went through your journey, people that you have to thank?

James Fish Jr.:

The one guy that I really think back on as being a mentor to me was a guy named Maury Myers. He had worked for Ford Motor Company, and then he'd moved from Ford to Continental Airlines, and ultimately ended up at America West Airlines because America West was having some trouble. And after undergraduate, I had gone to work for KPMG, as you said, early on. And then gone over to this little small airline called America West Airlines, which was kind of the forerunner airline of what is today American Airlines. And so Maury Myers came into America West Airlines.

And I really didn't have a mentor, so to speak, at the time. But Maury was coming in as the CEO, and I was pretty far down in the organization, but he was very approachable. And so I talked to him at one point. And then he kind of took me on and was my mentor for me. And he was the one that had suggested, when the company was in pretty bad financial shape, and he said, "What are you going to do with your career?" And I said, "I'd really love to go back to graduate school and I'm considering applying." And he said, "What kind of program are you interested in?"

And I told him about the type of program that I was interested in. And he said, "Look, I didn't go to University of Chicago." But he said, "I think that program would fit you very, very well." And he said, "If you're going to go and get an MBA, I would suggest you get it from a top two or three program in the world. And that is a top first, second, third in the world." And he said, "That would be my recommendation, would be University of Chicago."

So when I applied, and he had written a letter of recommendation to those three schools, I was thrilled to get accepted at Chicago. And it's part of why this distinguished alumni award is so meaningful to me because Maury was the first one, in addition to really knowing about the university as I mentioned through reading Milton Friedman, but Maury was the first one to say that would be a really good school for you. And so he was really my mentor. And when I got out of the university, he had kept up with me and he said, "Look, love to have you come work for Yellow Corporation." And then interestingly, I went to work for Yellow Corporation, and six months later, Maury jumped ship and comes to be the CEO at Waste Management.

And so I called Maury down here in Houston, and said, "You know, thanks for jumping ship there six months after you hired me at Yellow. Would you be interested in hiring me down there in Houston?" And he said, "Absolutely. Come on down." So that's kind of how I ended up getting to Waste Management. A funny, quick side note. I told my dad, I said, "You remember Maury?" And he's said, "Oh, sure." And I said, "Well, I'm going to go work for him." And he said, "Well, where is Maury now?" And I said, "He's at Waste Management, which is in Houston." And my dad said, "I think that business is run by the mafia." And I said, "No, it's a public company, Dad. I you've been watching too much HBO." But that was my dad's response when I first came to work for Waste Management.

Madhav Rajan:

So Waste Management is obviously a huge company. What would you say is sort of your leadership style, and how has it developed over the years, and what role, if anything, has Booths had to play at that?

James Fish Jr.:

Well, I mentioned there's a compassion at Booth that I think has carried me forward. And I'll just be frank about it, some schools, there's a bit of arrogance when you get into a school that has the reputation. And Booth could easily be that school, but it's not. I mean, I happened to be looking through the Nobel Prize winners. I just scanned the list last night. And it is incredible how many Nobel Prize winners have come from not just Chicago Booth, but the University of Chicago overall in all these disciplines. And honestly it's a school that could have this level of arrogance, but there is none of that. And so I think I took that with me. And part of that, of course, would have been hopefully my personality that my parents taught me.

But coming from a school that had every reason in the world to be pretty cocky, but it's not, really led me to my leadership style here at WM. I know that I'm the CEO of a company that's a pretty good sized company. But I also realize that there are 50,000 people that probably work a lot harder than I do. I mean, I know I'm the face of the company, but the people that make up this company are the people that really make it happen. They're the people that matter the most. I'm just out there telling the world about what we're doing, I'm out there whether it's on Squawk Box or whether it's yesterday on Golf Channel in Phoenix, all I'm doing is bragging on the accomplishments of the other 49,999.

And so I think a lot of what I learned at Booth is that while you, you want to study, and you want to educate yourself, and you want to make sure that you bring that to your position, do it with a sense of modesty. And I've always felt that the University of Chicago in general, and also Chicago Booth, really I think demonstrates that so well. And I've really tried to represent that as CEO of Waste Management.

Madhav Rajan:

You spoke about the first day you came to the university, is there any experience, or class, or a faculty member from Booth that comes to mind to you still?

James Fish Jr.:

There are a lot. I will say I never took a class from Eugene Fama, but one of my classmates did take a class from Fama. So I sat in it. And I don't think I was supposed to do that, honestly. I'm not sure. I think unless you audit the class, you're not really supposed to sit in. And he was renowned. Still is obviously. But at the time, everybody talked about him. And honestly, he was a little intimidating because of all of his accolades. He hadn't won a Nobel Prize in Economics yet.

But this friend of mine took his class. So I did sit in with him. And what I remember from the class, it was actually kind of funny. And he had an interesting way about it, but very matter of fact. Boy, if you weren't studied, and of course I wasn't studied for his class because I wasn't taking it, but if you didn't for his class, it became obvious pretty quickly. And so this class was largely comprised of PhD students. So I think the MBA students that were taking the class, we were kind of second class citizens there. And so the class, they were talking about asset pricing, I think, and efficient asset pricing.

And so one of the MBA students asked, "So I mean, beyond stocks and bonds, I mean, are things like artwork and real estate, are those also efficiently priced?" And so Fama looked at this student, and said, "Even that ugly shirt that you're wearing is efficiently priced." That is a great answer. And it was very vintage Professor Fama. But I think that scared me out of taking his class, not that I would have taken it anyway. He was on campus, and my classes were all at the Gleacher Center. But I think my fellow MBA student was like, wow, that was a tough answer.

Madhav Rajan:

Our students and our alumni always want to know, how do you balance your time? Sort of how do you manage your sort of work-life balance, if you will? What do you do to sort of reduce the level of stress that a job like this mistake on you?

James Fish Jr.:

I think it's important. I say this just from my own personal experience, and it might be advice for those who are watching, that you set your priorities in the right order. And so I say this all the time, and I said it in my note to all employees when I took this job, I said it even when I took the job out in Boston as a general manager running our operations out there, that my priorities in my life are in this order, faith first, family second, and job third. And the reason they're in that order, and I say this as well, is that while my job is very important, it's a distant third to the other two because the first two are just so important to me. I think if your priorities, whatever they are, and whether it's faith or not, but your job, at least in my opinion, should not be your top priority. And so I really try and prioritize my life in that way.

And my family realizes that there are times, this is one of those times a year, January, February, March, first quarter, it's a very busy time for me. And so they understand that, and they realize that there may not be as much of Dad around. So it becomes much more about quality time than quantity time. And then summertime, I do purposefully try and take time off and spend it with the girls. Tracy and I have two girls. One is a senior in high school, one's a sophomore in high school. And they understand that that Dad has a busy job, but it is important. Indra talks a lot about family. She talked about it yesterday. And I think as busy as I am at a Fortune 180, 190 company, she was CEO of a Fortune, probably, 25 company. And the demands on Indra's time were even greater. But she focused very heavily as CEO and chairman of PepsiCo on family time.

And I know Satya does the same. I mean, he definitely focuses on his family, even though he may be one of the most sought after CEOs in the world. The fact that he would agree to do our Sustainability Forum CEO panel was incredible to me. I was incredibly flattered that he would do that along with Doug as well, and Indra as well. And she still is very busy. But I think it's important that you have to set a balance there. And part of it is setting your priorities in the right order.

Madhav Rajan:

I'm going to ask you one final question, which may be a bit off the wall. I know that Doug McMillon began his career in accounting as well. Because I met him once at Stanford. And I know you did. And I was just wondering do you think that that helped you, being a CPA, going through the accounting training, has that been helpful to you in your career as a leader?

James Fish Jr.:

Absolutely. It absolutely did. Now I'm not going to say I enjoyed taking the CPA exam. I felt like they could test you on six feet of material, but the test was only a quarter inch. I guess not a quarter inch because you have multiple parts of exam, but there was so much material that you had to prepare for. I guess it was probably comparable to a bar exam. But I did feel like, and I was certified before I went through graduate school, that was hugely helpful in my finance classes. Obviously in my accounting classes, I felt like I had a leg up on some of the other students whose discipline was something different than accounting or finance. But to this day, I still use my accounting and my finance. Every day, I take something from the curriculum at the University of Chicago at Booth and apply it in some way, whether it is Ron Burt's class, which was not an accounting or finance class. And then there's a very funny story, if you have a few minutes, that I'll tell you about that Ron Burt class.

We were in his class, we had a project. And we're supposed to interview a high-level executive and talk about kind of organizational structure and things like that. So one of the guys that was in my class worked for United Airlines. And so we paired up with him. So there were four of us on this team. And so we interviewed John Edwardson, who I know has been a big supporter of the university, and was an alum from before us. So we interviewed him. He was president of United Airlines at the time. So we lined up the president, which was a pretty big deal. Some of the other groups lined up a vice president from a small company or whatever. And they filmed him with an old Sony camera.

First of all, John Edwardson did not expect this to be filmed in his office. So we walked in his office with him, and he thought we were going to just film it in a little conference room. His office looked like a Steven Spielberg movie set. And he was surprised. He said, "Wow, okay. I guess we're doing it in here." And I mean, they had two or three cameras. And so they filmed this interview. And then the video, my friend was also a Booth graduate who was with United Airlines, his name is Dave Wickersham.

And so Dave went to their editing room, and they put this thing together, and they had the “Rhapsody in Blue” song. And the opening of the video is this 747 kind of peeling off to “Rhapsody in Blue.” And then it kicked into our interview with John Edwardson. I think Ron Burt actually thought, did you guys take this to a professional and have it done? And we did get an A in the class. But he did ask. We said, "No, no, no. I mean, we did this ourselves and we helped edit it." Although honestly, I have to admit I didn't participate in the editing. That was all Dave Wickersham. But that was a funny story.

And Edwardson was very gracious to give us as much time as he did. He was president of a huge company like United Airlines. And it kind of goes back to that network that we talked about. I mean, when a student from University of Chicago calls the president of United Airlines, and he says, "Yeah, absolutely. Come on over," that doesn't happen, I think, at other programs. But boy, it was a fantastic experience for me. I'm flattered. So flattered that you've chosen me to be the Distinguished Alum here. And this was a great experience also having chance to talk to you about it.

Madhav Rajan:

Jim, thank you. Congratulations. Again, we are incredibly proud that you are a Chicago Booth alumni. And that you have done so well in your career, and made the school very, very proud. And thanks. We really appreciate you giving us the time today to do the interview. All the best. And again, thanks so much for your engagement back with the school, with the extent to which you and Tracy have supported the school, and be connected with us all the time. So thank you very much.

James Fish Jr.:

You bet. Looking forward to seeing you soon. Hopefully either up there in Chicago or down here in Houston.

Madhav Rajan:

I'll come to Houston, if you invite me to the Super Bowl.

James Fish Jr.:

All right. Deal. All right. Take care. Thanks a lot.

Madhav Rajan:

Bye.

James Fish Jr.:

Bye.

Shruti Gandhi

Founder and Managing Partner

Array Ventures

“My ability to stay ahead of tech trends is a result of my curiosity and ability to continuously learn. At Booth I spent time learning skills that I still use every day.”

When Shruti Gandhi, ’12, meets with startup founders seeking backing from Array Ventures, her San Francisco–based venture capital firm, she looks for founders who she can learn from. “In every meeting, I want to offer one thing they can benefit from,” she said, “and learn one thing I wouldn’t have learned elsewhere.”

The drive to round out her technical background with business skills led Gandhi to Booth after she earned computer-science degrees at Marist College and Columbia University. As an MBA student, she initially thought that starting a VC fund was for someone later in their career, but she was encouraged by faculty such as Ellen Rudnick, ’73, senior advisor and adjunct professor for entrepreneurship; Steve Kaplan, the Neubauer Family Distinguished Service Professor of Entrepreneurship and Finance and the Kessenich E. P. Faculty Director at the Polsky Center; and Mark Tebbe, adjunct professor of entrepreneurship. Now she is closing her third fund with support from the Booth community.

At Booth Gandhi served as chair of the student-led Entrepreneurship and Venture Capital Group, organizing visits by alumni speakers to campus. “Many of those people are now investors in my venture fund,” she said. “This ability to build long-term relationships is the power of our close-knit alumni network.”

Array Ventures invests in early-stage startups using data, A.I., and machine learning to help guide them to their next stage of business. That means Gandhi is constantly looking for potential—and she reminds Booth students that they have a lot to offer.

“As a student, you sometimes think you have nothing to offer to experts with many years of experience,” she said. “But you can stand out with your time, curiosity, and hustle.”

Starr Marcello:

I am delighted to introduce Shruti Gandhi, Chicago Booth's 2021 Distinguished Alumni Award winner in the Young Alumni category. An alumni of the Booth Class of 2012, Shruti is the founder and managing partner of Array Ventures, an early stage venture capital fund that focuses on solving pressing problems in large industries using data, AI, and machine learning. Shruti has led investments in over 60 companies with six exits to firms like Apple, PayPal, ServiceNow, and The We Company. She has also invested millions of dollars in startups led by women and founders from diverse backgrounds. Prior to founding Array, she invested for True Ventures and the Samsung Next Fund. Shruti also holds degrees in computer science from Marist College, and Columbia University, where she also serves as an adjunct professor in the computer science department. She has been featured in the media in a number of outlets including TechCrunch, the Wall Street Journal, Business Insider, the BBC, Forbes, VentureBeat, and USA Today. Congratulations Shruti and thank you for chatting with me today. So—

Shruti Gandhi:

Thank you so much, Starr. I'm so excited to have this opportunity. Yeah, thank you for doing this.

Starr Marcello:

Thank you. So let's just get started. Why don't you tell us a little bit about Array Ventures and your role as general partner and founding engineer?

Shruti Gandhi:

Array Ventures is a B2B SAAS enterprise fund. We like backing founders in their early journeys, as soon as they're thinking of starting a company, as they're leaving their jobs. Array comes in and helps them figure out how to get from what we call the 0 to 1 to 10 journey. When we invest there at 0—no revenue—we help them get to one million ARR. And then from there, we help them set up for a 10 million ARR journey, which is when all the work that is required around that around marketing, sales, and so forth gets happened. And then after that, we help them get to the following round of investors, usually all the top central firms such as Excel, Sequoia, Norwest, and others who followed on after us. So we're pretty focused in our thesis and in the market of where we belong. We believe that as I started my journey, I built and started a company, I wanted that help from a firm like ours and I thought I should go start one.

Starr Marcello:

Thank you. You commented on Booth. So I want to dive into that a little more. You've clearly made huge strides as a leader who is supporting women of color in an industry where women are highly underrepresented. I would love to hear more about your career path, the path that led you to Chicago Booth, and how the time that you spent at Chicago Booth shaped where you are today. So could you tell us a little bit about what experiences and groups played a role for you during your time here at Booth?

Shruti Gandhi:

Yeah, so first of all, I have to give a big shout out to Ellen Rudnick. Ellen, without Ellen, I wouldn't be at Booth. She has been formative in terms of how I got accepted. And also since then after that not only with the classes I took, the first class I took with her was the PE/VC lab which is where I ended up working at a local Chicago venture firm at that time was called I2A Ventures. I believe they're now called Chicago Ventures.

Starr Marcello:

Yeah.

Shruti Gandhi:

So that was my starting point. As someone would never even spend any time in venture capital before, that was an amazing opportunity for me to be able to go work at a firm and learn all the different pieces of what it means to be in a venture business. And then also in the classroom, discuss all that in a safe space and learn from experts, from classmates and my professors too about all the things that I was doing right or wrong. From there on, I worked at Lightbank as well. And that was an amazing time as well. Obviously at that time, Groupon was really, really on the up and working directly with Eric and Brad at Lightbank was also interesting experience.

In fact, one of the deals I actually helped bring on their radar, there I ended up doing that deal and eventually eight years later, I ended up backing that founder again at Array Ventures. So that is how, I guess, this world works. It's a long journey. It's a marathon, not a sprint. And those relationships you cultivate even at Booth and throughout your career are so valuable. And I can continue with the clubs. So then for example, I was a chair of the PE/VC club. And that was obviously how Starr, you and I interacted so much.

Starr Marcello:

Yeah.

Shruti Gandhi:

And I went in NVC and bugging you all the time. I think you were so amazing at just listening to all our raw ideas and helping us make sense of it. We were sitting in the Polsky Center and you guys were available. I remember so many of those conversations in your office about—even since then, after I graduated coming to your office and saying, "Hey, Starr, I'm starting a fund. Who should I talk to? How do you think I should think about this?" And then you would generously give your time to me. I mean, this is the power of being at Booth.

We're all independent thinkers and giving each other a fair chance, which is still important because when you were about to start something new, there are enough naysayers and enough people out there that look at you and say, "Come back after five years when you have enough experience." And that enough is never enough. But folks like you looked in my eye, including our professors like Steve Kaplan, Mark Tebbe, and so—and Waverly—and many others looked at me and said, "Look, I think you can do this. Here are all the downfalls, and here's why it wouldn't work. But if you do this right, I'm willing to back you." And that's what people did. So I think that's the power of our Booth network. And I can talk about more clubs and so forth, but I'll pause for now and yeah.

Starr Marcello:

Well, I appreciate those very kind words. And I think you inspired all of us as well with your ideas and with your commitment and your belief that you could go ahead and start a new fund and be successful. Your conviction is really inspiring. I want to go back to just one comment you made. And I feel I have to do this after spending 15 years working on the New Venture Challenge. You mentioned that this program for us has been recognized more recently as a leading startup accelerator in the United States. And we've seen many hundreds of companies come out of it. This year in particular is a special year for that program. We're celebrating the 25th anniversary of the NVC. And I am curious if you think back on your time—of course, we're going to talk a lot more about your time now as an investor—but the NVC of course really focuses on the founder and the founding experience and the connection with investors. I'm just curious if you have any reflections on your experience going through that program that would be inspiring for our alumni and also our students to hear?

Shruti Gandhi:

I was so scared. NVC was honestly a time of my life where I thought, you know, I was so scared to put my ideas out there especially in front of so many amazing investors that are out listening for you to pitch something that they could invest in. So when you're in NVC, it's live experience basically throughout as what you would be feeling and doing outside in the real world except the thing I learned halfway through is, they're not judging you. They want to help you. And that's the power of NVC. I remember people filling in forms with copious amount of details on what I should do better in my business model and things. And at that time, I could look at that and say, "Wow, this is scary." Or I could look at that and say, "Wow, these people want to help me." And that was a powerful thing I learned that impressed me so much that people are dedicating their time. They want to help me. And then they are taking the time.

I remember spending time with Mark, and I—These are some amazing successful people that are dedicating their time to someone like me and hundreds of students like me just without any expectation of something back. And that is what has actually helped me create one of the values at our firm, which has always helped people out regardless of their idea and the stage they're in because people in itself have potential that you can never see. Sometimes people amaze you and maybe the idea they're working on right now is not the best idea. That's okay. It's a relationship with the people that matter. And that's what I learned a lot at NVC and at Booth generally. So I don't... There's a lot more to it and the process is amazing as well and it kind of helps you think about every different part of your business, but these are some of the soft things I learned that I have to really—that I can take away for the rest of my life.

Starr Marcello:

Thank you. Yes, and hopefully, they've been helpful as you apply those values and those thoughts to your current firm. So I want to ask you something else sort of inspired by Booth. There is a neon sign in the halls here at the Harper Center that says, “Why are you here and not somewhere else?” And I'm curious to hear from you, what is your why, what do you seek to accomplish and what kind of impact are you looking to make in the world?

Shruti Gandhi:

That is such an amazing impactful sign. You're right. I have since then quoted and looked up that sign many, many times. And that is a simple thought that really if you are actually serious about that thought, and if you take the time to evaluate this, can help you guide every decision in your life. And that helped me figure out why am I here is not somewhere else after business school at Booth, I ended up coming to the Bay Area. At Booth, everyone was doing all sorts of recruiting, but I did not want to do that. I was still very persistent on the venture entrepreneurial path. And beyond there, I think all those decisions have been impacted by “why are you here and not somewhere else.”

For me, I was in New York. I'd already had all these degrees and I should have arguably just gone to work, but I knew what I needed and what was lacking in my background, in my experience, in my network and from a point of just knowledge as well. And to me, that was the decision that I made while I had so much angst of I'm losing experience and time as someone who would already worked for a decade. I was feeling that anxiety of why am I here and not somewhere else, but that is a sign that kind of helped me ground myself as to I'm fulfilling the long-term goals for my life of what my mission is. And to me, that is more important than a short-term job that I could be taking right now. And look at me, my career transformed.

Before that, I was an engineer and I started a company, but everyone asks me how one gets into venture capital. And the one single answer for me is Booth, which is not the same answer for everyone else, but for me, that is the one single thing that helped me get there. And to me, I think that sign is a good reminder of that. And so then the next experience of why the Bay Area, at that time, I was in tech. I wanted to be in the Bay Area because I knew that is where all the enterprise data, AI machine learning kind of funds, a decade ago anyway, things are changing in Chicago as well now, but were here.

So I wanted to be here. And despite not having a job lined up or anything else, I moved here, slept on people's couches, and then ended up actually getting a senior role at the Samsung Next Fund, which I helped start in the early days. So that I think is a good reminder of why was I here and not somewhere else. And it was a very thoughtful decision for me that I had to make reflecting on those basically that seed that the sign had put in my brain. So I would say that I want a copy of that sign. I know it's a great amazing artist somewhere, but I want that in my house at some point soon.

Starr Marcello:

Yeah, thank you for sharing that. I would love to hear you talk a little bit more about some of the pivotal moments in your career, because in the roles that I've had here at Booth, I've certainly heard other students aspire to start their own VC fund one day and be able to do some of the things that you have done. But very few of them do it. And certainly, very, very few of them do it in the timeframe in which you did it. And you had the confidence to make your way out into that part of the country that you believed you would be successful. You were willing to sleep on couches. You were willing to pursue the dream that you had. I can't imagine that you got to where you are now without challenges, without some bumps in the road. And I would love to hear if you're willing to share just some of those pivotal moments and how you dealt with them.

Shruti Gandhi:

I'll tell you one moment that is so, to this day teaches me a lesson. Summer between my first year and second year at Booth, I was interning at a fund here in the Bay Area. And that was the first time I ever lived here because that was my journey, I was starting too, after Booth, I want it to be this kind of a journey, and I was working hard and somewhere along the lines, I learned about this program called Kauffman Foundation Fellowship for budding aspiring VCs. And I thought—this is the example of me learning, Shruti learning 100 times. I knew Professor Kaplan was involved and was in the board at one point, but I was embarrassed to ask him. I was embarrassed to say, "Hey, could you put in a recommendation?"

I thought only the best students get picked by the professors and then basically they'll back you in ways that they would want. I never thought it would be something I as a student should ask my professor who was so amazing and so forth. So I did not ask him. In fact, I learned about the deadline after it had passed. And what did I do? I was here in the Bay Area just talking to a lot of venture firms. And I just randomly, I was shadowing someone at NEA, and I learned that one of the partners at NEA, Patrick, was also involved in the Kauffman Fellowship. So I had no relationship with Patrick, but since I was there, and I'd been interning there and he'd seen my work, I felt comfortable of asking a stranger over a professor to put in a recommendation and take my application despite the deadline passing.

I come back and I'm taking this entrepreneurial finance class with Professor Kaplan. I'm sitting there and after class, first class, he comes and tells me, "I'm really upset at you. Someone's calling me and telling me that one of your students has applied to this program, and I have no idea about it. And you did not inform me, and I'm caught in the dark here. And that's embarrassing for me." And I was like, "Well, I'm sorry. I didn't want to take any favors. And I didn't want...If I had one favor to take, I would save it for something really, really important." And he was like, "Nope, that's not how it works. The way it works is you ask. And if people can’t do something for you, they say no, and you don't take it personally."

And that is one big pivotal moment in my life. I still remember that classroom. I still remember Professor Kaplan, you know, in his style telling me, "Look, be out there and do it right, and keep all the people around you informed. You are a part of this institution, and so you should have been telling me." And that lesson is one big pivotal moment of asking first, and not taking it personally and “no”s are not, again, those are not something you should take personally and it's not a permanent no. And keeping people in your journey involved.

And it takes a lot of work. But it's important because that is why I tell, I email you once in a while and say, this is what's happening. Here's what I'm doing. I'm starting my next fund. It's for someone to call, who was about to make a call to you because they know I went to Booth and say, "Hey, do you know this woman, Shruti?" And you're going to say, "Yeah, but I haven't talked to her in a while." Versus, "Yeah, I just talked to her." And that's the difference. So that was a big moment in my life. Since then, I think I can continue down and I am—sorry. Are you going to say something?

Starr Marcello:

No, no, go ahead. Go ahead.

Shruti Gandhi:

Right, I think since then, I have to think more about the big pivotal moments, but there...I know it's more like people think about the resume has pivotal experience and that is true. That is always true that you want a great experience at a great firm. But for me, it's the softer learnings that I have developed in these moments of: Let's just go for it. And what's the worst thing that's going to happen? I took a lot of classes at Booth. My last two semesters were basically focused on organizational behavior courses under Linda Ginzel and Professor Greg. And the classes were called decision-making and all sorts of different names on decision-making. And when I entered Booth, the two things that softer side that helped me...

So the first story I told you was this, the power of putting yourself out there. Two, was the decision-making and that is what Booth is really good at. Making decisions based on data you have, and you can never have enough data. And there's always going to be more data as time passes on. But the “strike when the iron's hot” is a real phrase. Momentum is an important thing to learn where, you can get the experiences down the road, but you have the opportunity now to do something big. So why did I start my venture firm when I did? I was in venture for about five years by the time I'd left Booth or about four or five years. And I had started getting some really early exits in my career at Samsung and True.

So I was thinking that was something people do years down the road. I was thinking, I was undermining myself, I was thinking that's what you do once you have a lot of IPO's and things like that. So never thought that I would be the one starting a firm. But when I started to, left True to start something else, my founders basically that I'd worked with came to me and said, "Hey, look, we loved working with you. There are not enough investors out there that are technical and also have a venture experience and a good all property background. So if you're investing in things, we liked the way you look at the world. We want to invest with you."

One thing led to another including a lot of our professors like Steve Kaplan, Ellen Rudnick, Mark Tebbe, who said, "Yes, we want to back you. We saw... We want to take a chance on you." Basically, that's all you need. Someone saying that and that gives you the confidence to say, I can do this. I have in me to do this. Even though I thought this was something people, gray haired men do it in their 50s, I can do it now. And there were people who basically enabled me with their words and support and their capital, which is super important. So that's what kind of led me to start the fund.

And honestly, five years in, I still believe that is a necessary need in the market. There are not enough enterprise funds out there. And actually, I feel like I started a trend. There are enough folks now that have started a fund based on no experience, but just different backgrounds and networks and so forth, that I feel like in some ways I felt like I was early in the game, but now I feel like a trend-setter, even though I may or may not have been. But I do feel like my life, I put it out there for lots of people to be inspired by because in some ways, as my last name, a famous person with my last name said, "My life is my message." I tried to live that life because if I do something out and put it out there, then someone, a little Shruti somewhere in the world looks at that and says, "Wow, she just did it and she didn't have that background. I can do it too. I don't have to go to all the top networks and universities and so forth to make that happen." So anyway, it's a long winded way of answering your question, but I hope I did a okay job.

Starr Marcello:

It was wonderful. I think the thing that really struck me hearing those stories that you shared about pivotal moments in your career is really something you said earlier too, the power of people and the power of relationships and asking for favors or asking for connections or really utilizing the community around you. And building on that, I want to ask your perspective about being an alumni of Booth. We have 56,000 plus alumni all around the world and this is obviously a powerful and dynamic network. What does this network mean to you? What does it mean to be a part of this alumni community now?

Shruti Gandhi:

Honestly, I have...This is so cool though. When I came to the Bay Area and as I said, I basically didn't know more than maybe five people even. The people that ended up being part of my close network and backing me early were also Booth alums, which is crazy because as a PE/VC, one of the chairs, I was bringing in speakers all the time. And again, it's about asking, and I know when we have the big conference, I know that it's in January, February, in the middle of winter and I was...One thing could be like, who wants to come to Chicago? But the other thing was like, why shouldn't I ask them?

So I had some of these people like David Wells who was at Kleiner at the time, Brad Burnham, Union Square Ventures, Phil Black, True Ventures, [inaudible] who was an alum of Booth, [inaudible], I asked all these people to come speak without ever knowing them. And they did come. They came and now they remember me years later. And a lot of these are my backers. These are people like David Wells, 10 years later, just backed my next fund. And he remembered coming to Chicago, and being on this panel that I thought was a small thing, they get invited to do so many big things, but they came. They came to talk to 30 students in a class or in a PE/VC club. And that matters.

And that our alumni...I forgot to mention Prashant Shah. These are some amazing folks who came and what I did was try to make their time valuable. So I would try to find amazing professors who would then spend with them after their talks and so forth or smart students, my classmates, who then would want to have something more to offer than just me. And I did that and I never thought of anything of it. In fact, I didn't even think people would remember. But a lot of these people, most of these people are now backers in my fund, and I never knew that was what it was going to happen. I was going to start a fund and all this other stuff, but this is what the power of, again, the power of our alumni network and also the power of our brand, is what you could take advantage of as an alum. And I always have. All these, you have to...

I also believe in giving back. And so I try to always give back in the ways I can as well—with time, with whatever, coaching. And I've been involved in the global NVC and all the other good stuff we've been doing. But I think that, giving back, and also not being afraid to ask people, and then making it worth their time is powerful. And then our alumni group, I think there was an article that I put out there. I think the Chicago Magazine put out there. I think I put all the people that have always helped me in our community. The cool thing about the alum community is—this is the part I love the most about our students and anyone who's gone through Booth—is, it's like people that are practical, they're transparent, they're straightforward, and they're willing to help. And I think that is unlike any other school and set of folks I meet. There's no, I would say like the BS factor.

And there is this, I've been here, I've seen your journey. We all came out of university that we know what our ethos is. We're all independent thinkers. We don't go based on momentum. We have grounded fundamentals. Those are some of the things that really I value a lot from my education there, but also from our alums that have now, I would say, I can count on a lot of these people as my close confident community of people I go to. As I am building out, I would say I'm still in my early days of building out my firm, my journey, my career. And these are people not just helping me in my fund, but in my career, and helping me be a certain…They're my sounding board. And I literally can call them, text them at any hour of the day and they're everywhere in the world. So they pick up the call at any hour, answer my question, and they do the same with me. And I love the power that community have.

Starr Marcello:

Thank you. So at Chicago Booth, we talk a lot about the Chicago approach and that includes not telling students what to think, but telling them how to think. And I'm wondering if you could talk about how that has played out for you in the things that you have done in your career or maybe as a person, have you adopted that approach? Have you found that to be a useful way of looking at the world?

Shruti Gandhi:

Yes, I think that is what I meant by when I said independent thinkers. I think the how you think is what gave me the confidence because you have this grounding of the three-legged stool, you have the stool legs if you will. What that gives you that confidence of one, there's the fundamental needs in the market. So you validate all that. And two, you are the right person to go tackle the problem, whatever the problem you're tackling. And that framework as you mentioned, of not tell you, but help you, give you the tools is why I am here today. There are many times, as you said, I would have been questioning, even yesterday or the day before questioning my approach, questioning...

Always there's something in the market that is not true to your ethos. And an example of this would be like in my fund, there's always a momentum driven investors, not in my fund, sorry, I meant in venture industry, there's investors who will just go and buy logos and that's how they build their brand. And there are investors who fundamentally spend time with the founders, help them grow their businesses ,the way I talked about the 0 to 1 to 10 ARR approach. It takes time, but I don't know any other way. And I think that is what Booth has taught me to be grounded in who I am.

It may not be the right answer for someone else, but it is a right answer from me to help me figure out what I like to do, what's an impact I'd like to make and why did I start the fund to begin with, which is a big answer of...Actually that clarity I got at Booth. Otherwise, I wouldn't be pursuing a path that most people feel like they can never even get into, which is venture capital, to begin with. So yeah, that's what I have to be really thankful for to be this person...I tell people, I tell my husband, who I met after Booth, that I am this different person than I was before business school. And it is all because of what Booth has taught me, in a good way.

Starr Marcello:

Yeah, that's wonderful. I'm wondering, Shruti, can you tell us what does winning this award, the Distinguished Alumni Award mean to you?

Shruti Gandhi:

I don't think it's a Booth-level answer honestly. Sorry, it's an answer that is a personal journey answer for me. I don't know if most people know this, but I couldn't even get into a college in undergrad. I came here after my high school and my parents decided to kind of like...We immigrated here as a family, and they left me in a month. And they said, figure out everything, including getting into a college somehow. And I didn’t have—we didn't know about SAT scores or anything like that. So the power of getting into a college and the way I did that by the way quickly is was I taught myself how to code. I got into Marist College by basically showing them the work I was doing already at the university in the computing lab, because I taught myself how to code and joined their lab.

And then yeah, they took me in without the SAT scores. But to that day, I was like, wow, what would my opportunity have been if I actually had a fair chance to everything? So then after that I went to Columbia and got my Master's there. That was an amazing moment as well. And I was working throughout all of this, undergrad too, by the way. But then when Booth ended up accepting me, I think from there till now, from 20 years ago till now, this journey kind of in some ways, even though we should not be looking for validation, validates me as to, the hard work has paid off. I'm here today. There are people who care about my journey, and Booth cared about my journey.

They accepted me first of all, based on I was not a typical background. I was never a straight shooter, because I didn't know how to be one. I just didn't have that coaching and mentorship—before Booth. So then I just was figuring it out on my own, and Booth took a chance on me. And now you're taking a chance again on me by giving me this award and having me represent Booth in the world out there. So I feel like that kind of support means a lot for someone like me who had not even a penny in my pocket at one time and people who only want to back you on until you become something big. But what the Booth community has done is said, I know I see something here, and they see it before I see it in myself sometimes, which is a powerful thing.

So this award means to me kind of a validation, a checkbox which again, most people shouldn't look for all this. But for me, it means a lot from one of the top universities in the world that people try to get into is recognizing someone like me for all the work I've done. That means that you—and you see a lot of students come through every year. So for me, the way I took it as you're validating all the things I'm doing, and you're saying go Shruti, go and make it happen. We're here for you. And that community and the village behind you is powerful, because marching alone, you can only get this far, but marching together, you go very, very far. I don't know. It's a very famous proverb from somewhere. I did not make it up. But that's the belief I have. Yeah, and this award means a lot to me.

Starr Marcello:

It is remarkable hearing your journey, how strong your entrepreneurial spirit has been from a very, very young age. And incredible that you were able to navigate your way to college with very little resources and then to graduate school at Columbia and of course graduate school here at Booth. Thank you for sharing those comments. I would love to hear maybe just based on your extraordinary journey, what advice would you have for our students today? They are the future leaders in the business world and in the public sector world in some cases in many different ways on many different paths. And they are very keen of course on making an impact on business and on society. Do you have advice that would be helpful to them as they embark on careers as future leaders in the world?

Shruti Gandhi:

It's a big question. I mean, there's so many things that come to me. Again, my advice is going to come based on my experiences. So I think everyone should take it lightly and make a sense of it in their own ways. But to me, I think there's a big lesson I've learned along the way. It’s that you have the power. The power is within you. And I'm going to pause for a second for us to register this a little bit because I did not know that. And when you are already at one of the top schools in the world, you have the power. You have the power of the brand backing you, you have the power of your community supporting you, you have the power of knowledge that you're getting there that you wouldn't get anywhere else.

You're around these, I mean, Nobel Laureates that have achieved so much. And even if you don't take classes from them, you know that the air around there that your being, has this knowledge and you're immersing yourself into it and you should. The power is, though, being able to recognize that and then translate that into anything else you're trying to do with confidence. And what that means to me particularly is I use that power to go reach out to all these people. But not just say, not just randomly calling out on these people and saying, give me your time. But more importantly, I took that power to create all sorts of analysis in my industry at that time. And I validated it in my classes with my professors, in the case studies I was learning from, all the venture and classes I was taking.

And I basically from there on use that as a...Because I think when you are as a student and in that environment, you think you have nothing to give. And what I learned was I had the power of knowledge that others may not have because not everything is equal. Others are successful for different reasons. So I use that. I packaged it. And when I reached out to these people, I said, here's what I have to offer. And that is what I keep telling people. You have the power within you to give at whatever level you're at. Even if you have no education, you can give your time, you can give your resources, you can give your hustle.

There's a lot you can give. People want to recognize good potential in other people and help. And I think you just have to show that you have it in you. So that is the biggest lesson for students to say that you have the power within you to one, show what you have and then be useful to someone else. And that is how you get opportunity to connect with some amazing successful people who see that potential in you through your work. Otherwise, how are they going to find you? And so that is the biggest lesson and advice to give back. Do the work, share it, and don't be hesitant to make a community out of it.

Starr Marcello:

Thank you. Shruti, when you were a student, is there anything looking back that you would have done differently or do you have any favorite memories of your time at Booth that you could share with us?

Shruti Gandhi:

What would I have done differently? So many things. I think there are things that when you're in the journey and especially not many people who are doing venture capital as a career at the time, it was hard to be in the groups like consulting, banking, where you just get to really meet a lot of people and get to know them at a very different level outside of the cohorts and things, the LEAD groups we have. And so I think I don't know what I would have done differently other than the fact that I think I would have maybe created more of a community around my work to enable, so people understand because the funny thing is to this day, my classmates reach out to me and they still don't know what I really do.

Then I know. But these are folks that are successful in so many other things they have done. So I think that community would have really been... And again, you guys have created that community at Polsky, but I would have done a better job of doing those kinds of like bonding sessions that the consulting and banking other groups have, which is like a case study preps and things like that. So that's one thing. I don't know if it's a...That's just a personal thing. And what else would I have done? I don't know. I feel maybe I would never...I don't think anyone should ever feel like, I would have said I would have had more fun. I would have gone to more TNDCs.

But which, at that time looking back, it was like, oh my God, I have to go do this interview and do talk, create this point of view for this [inaudible], trying to talk to this partner and before that I want to share this data, big data, and SAAS and all these other industry point of view and…All that takes time. And that comes with a sacrifice of all the social things that you might want to do and you should do because that is what business school is all about. So that's I guess two things I would do a little differently.

Starr Marcello:

Yeah, do you see yourself as a lifelong learner? And I'm just curious how your time since you were here at Booth, how you continue to learn at the stage in your life that you are in now?

Shruti Gandhi:

I think your life ends, your career ends I should say, not life ends, career ends, if, the minute you stop learning. I think the power of being a good investor is the ability to learn as fast as you can from a meeting or two. So I think I would not claim that I'm the best technical person out there today. If I am talking to a founder and if I know more than they do, I do not invest. So the fun of my fundamental life rules is when I take a meeting, I want offer one thing that they can take away and say, I learned it from this meeting and I want to learn one thing that I would have not learned somewhere else. And that is why those pitches are so fun for me because I'm learning. So that's one medium for me to learn.

The second way of learning is actually, believe it or not, publishing a lot. I publish, write a lot and there is inherent fear we all have, which is, oh my God, I don't want to put something dumb out there. And that makes you want to go research a little bit more and read more and see what others are publishing. And so you end up being very knowledgeable just by the fact that you have this fear of not producing something where your peers are going to laugh at or feel like you're not innovative enough in your thinking. So that's the two ways I would say in my pitches and make sure I learn a lot. And those are the kinds of founders I back where I know I'm going to continuously learn for the next 10 years. And then in through the writing I'm doing, it brings the clarity of thought into my thesis, my approach I have in what I want to invest in and things like that.

Starr Marcello:

That's wonderful. Thank you. I just can't help, but think back to the time that we spent together when you were here as a student and what the Shruti then would think about the Shruti now and as the recipient of this Distinguished Alumni Award. And I just marvel at all the progress that you have made and can't wait to see what the next 10, 20, 30 years look like for you. Thank you so much, Shruti for sharing your thoughts with us and congratulations on this wonderful award. Thank you.

Shruti Gandhi:

Okay, before we close, I want to say, thank you, Starr. You have been personally so impactful to me in my journey. And as I said, you have a lot of students asking for your time and help and you have been phenomenal with being that comforting room that I could go, close that door and just sit down and tell you all my fears and struggles at the time. And you not looking at someone like me and saying, one more student asking for my help, but more like, what can I do to help, which as I said, empower someone like me. So thank you so much for that.

Starr Marcello:

Well, if we get more Shruti’s here with brilliant ideas and the commitment to change the world through entrepreneurship venture capital, it will be wonderful for the school. And I hope that your story and everything that you have shared with us serves as an inspiration to many, many people. Thank you.

Shruti Gandhi:

Thank you so much for the award, and I really appreciate you guys recognizing all the work I've done.

Starr Marcello:

Thank you. Wonderful.

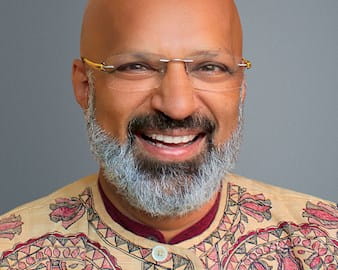

Luis Miranda

Chairman and Cofounder

Indian School of Public Policy

“When people come to me with a business idea and say it’s going to make a billion dollars, I immediately tune out. What I want to know is, how is this going to make people’s lives better?”

Luis Miranda, ’89, likes to compare himself to Forrest Gump, the movie character played by Tom Hanks who unwittingly influences significant events in history. “I’ve been lucky that people have given me opportunities that led to this fascinating journey,” he said.